Picasso and Antiquity

Line and clay

DEVINE DIALOGUES

JUNE 20 UNTIL OKTOBER 20, 2019

THE EXHIBITION

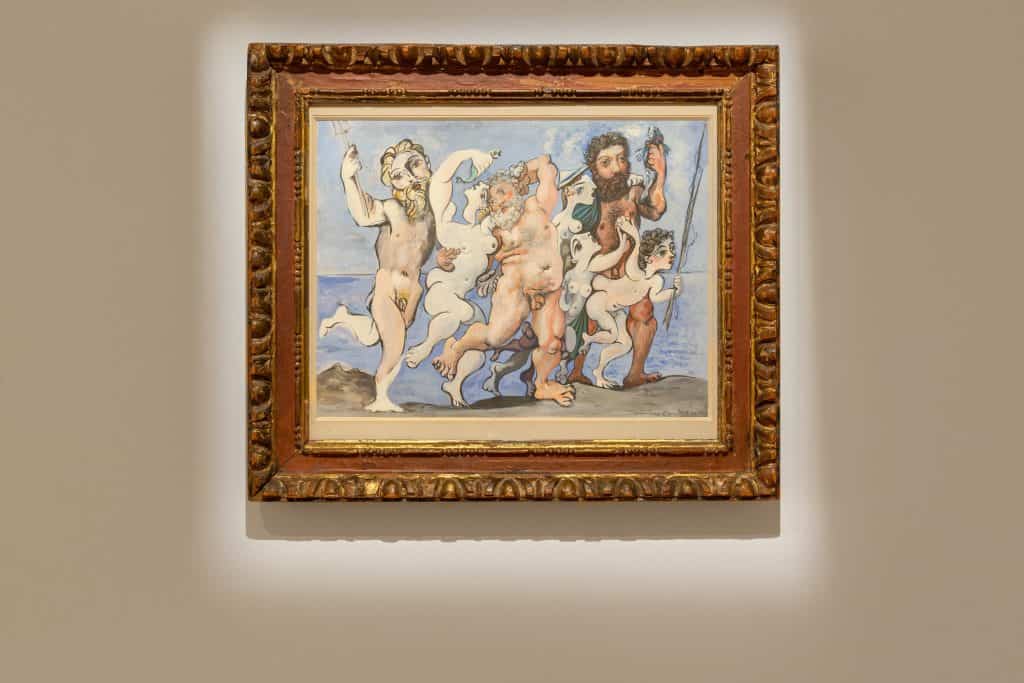

Sixty-eight rare ceramics and drawings by Picasso, featuring birds, animals, sea creatures, humans, and mythological beasts (centaurs, the Minotaur) or inspired by ancient drama and comedies, conversed thematically for the first time with sixty-seven ancient works, creating another Divine Dialogue between Greek antiquity and modern art.

Unlike his unique paintings, the great twentieth-century artist’s drawings and ceramics are little known to the wider public. These are closely related to antiquity, inspired by the Creto-Mycenaean, Greek, and ancient Mediterranean civilizations in general. This exhibition revealed a world the artist carried within himself, showcasing antiquities that he might have seen in the ancient lands of the Mediterranean, but also in European museums, in the books he read, or during his encounters with Christian Zervos and Jean Cocteau.

Throughout his long and productive career, Picasso consulted a wide variety of sources, adapting and transforming them relentlessly. The Classical tradition provided the Spanish master with a vocabulary of endless possibilities to be manipulated and modified. Prominent among these sources was ancient Greece, for it created an enduring mythology as well as a fertile iconography. From the time he copied antique plaster casts in his youth, Picasso was seduced by many themes derived from Greek mythology, drawn by their amplification of the mundane or their persistent aspiration to highlight humanity’s conflicting impulses. The Minotaur, for example, this Dionysian creature, half-beast, half-human, symbolized the dark regions of the psyche, becoming a telling symbol of the irrational forces of war.

Another, more benign vision of Greece emerged as well, one in which the ancient themes and stories lead to an idealized vision, a timeless Arcadia, which Picasso developed in sculptures and ceramics after World War II. Yet, these works, unlike some earlier ones, are devoid of weighty associations with Greek myth. Rather, Picasso invented a fictitious or imagined antiquity. In the small village of Vallauris in the late 1940s and 1950s, he developed an extraordinary body of ceramics, objects that give us a vague idea of a mythical past, imbued with timeless and relevant imagery in the form of fauns, birds, musicians, etc.

The element that binds both ceramics, old and new, and Picasso’s illustrations derived from the antique (the Three Graces or Aristophanes’s Lysistrata) has to do with form and design, and not just iconography. Of particular relevance is the line, whether in drawings from the 1920s and 1930s or the lines traced on ceramics and reminiscent of Attic Red Figure vases, for example. Picasso and Antiquity | Line and clay exhibition demonstrated the force of Picasso’s both imaginary and personal reading of antiquity, and the lasting spell that objects from the past cast on us.

THE ARTIST

Unlike his unique paintings, the great twentieth-century artist’s drawings and ceramics are little known to the wider public. These are closely related to antiquity, inspired by the Creto-Mycenaean, Greek, and ancient Mediterranean civilizations in general. This exhibition revealed a world the artist carried within himself, showcasing antiquities that he might have seen in the ancient lands of the Mediterranean, but also in European museums, in the books he read, or during his encounters with Christian Zervos and Jean Cocteau. Throughout his long and productive career, Picasso consulted a wide variety of sources, adapting and transforming them relentlessly.

The Classical tradition provided the Spanish master with a vocabulary of endless possibilities to be manipulated and modified. Prominent among these sources was ancient Greece, for it created an enduring mythology as well as a fertile iconography. From the time he copied antique plaster casts in his youth, Picasso was seduced by many themes derived from Greek mythology, drawn by their amplification of the mundane or their persistent aspiration to highlight humanity’s conflicting impulses.

The Minotaur, for example, this Dionysian creature, half-beast, half-human, symbolized the dark regions of the psyche, becoming a telling symbol of the irrational forces of war. Another, more benign vision of Greece emerged as well, one in which the ancient themes and stories lead to an idealized vision, a timeless Arcadia, which Picasso developed in sculptures and ceramics after World War II. Yet, these works, unlike some earlier ones, are devoid of weighty associations with Greek myth. Rather, Picasso invented a fictitious or imagined antiquity. In the small village of Vallauris in the late 1940s and 1950s, he developed an extraordinary body of ceramics, objects that give us a vague idea of a mythical past, imbued with timeless and relevant imagery in the form of fauns, birds, musicians, etc.

The element that binds both ceramics, old and new, and Picasso’s illustrations derived from the antique (the Three Graces or Aristophanes’s Lysistrata) has to do with form and design, and not just iconography. Of particular relevance is the line, whether in drawings from the 1920s and 1930s or the lines traced on ceramics and reminiscent of Attic Red Figure vases, for example. Picasso and Antiquity | Line and clay exhibition demonstrated the force of Picasso’s both imaginary and personal reading of antiquity, and the lasting spell that objects from the past cast on us.

THE INSTALLATION

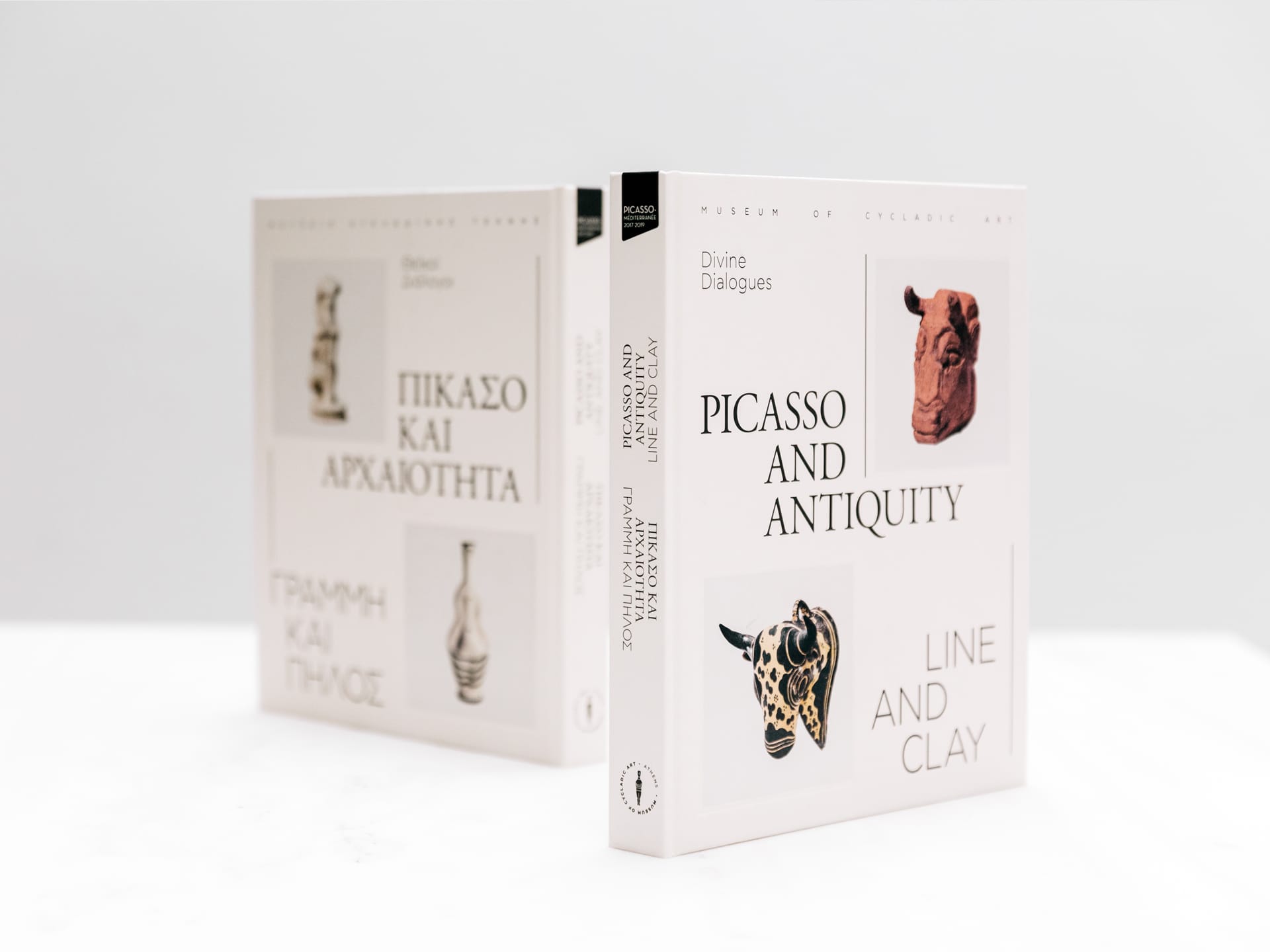

EXHIBITION CATALOGUE

The exhibition was accompanied by a Catalogue that issued as part of the series of art exhibitions “Divine Dialogues” for the exhibition “Picasso and Antiquity. Line and Clay” with analytical explanatory texts and copious illustrations.

Curated by

Assistant Curator

Exhibition Design

Mounting of Artworks

Exhibition Constructions

Picasso Artworks Condition Reports

Translations

Visual Identity

Artworks Transportation

Insurance

Sponsors

Official Air Carrier Sponsor

Hospitality Sponsor

Legal Advisor

BECOME

FRIENDS