Greece between two worlds

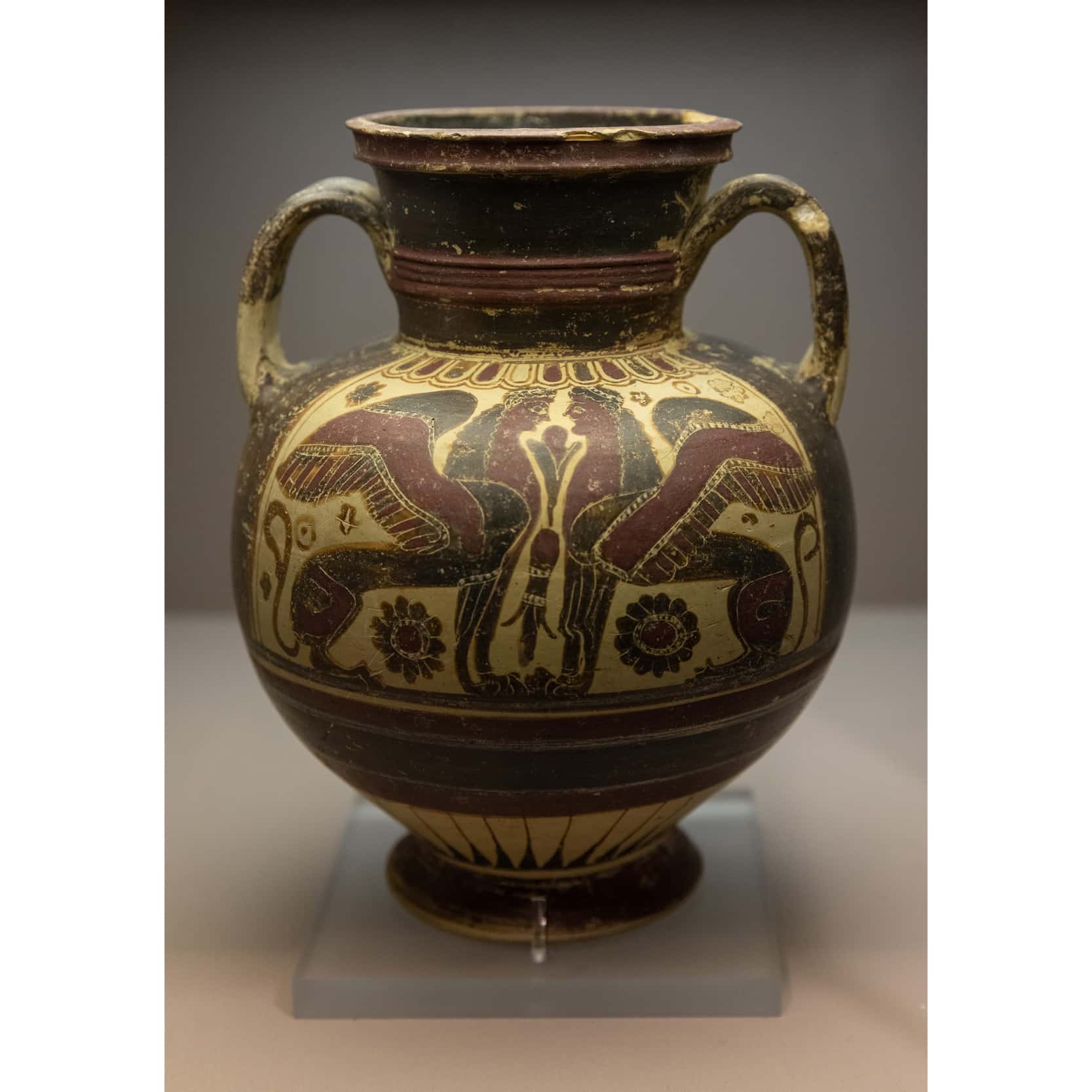

ANCIENT GREEK ART

THE SITE

At its height, Greek culture was spread out over a large part of the Mediterranean and a good portion of the ancient Near East. Its cradle, however, is found in the Aegean.

This closed sea, which covers an area of approximately 200.000 square kilometres and separates mainland Greece from Asia Minor, was a major route of trade in antiquity and the location of creative encounters between the East and the West.

GEOMORPHOLOGY

Apart from the extensive plains of Thessaly and Macedonia – which were not thoroughly exploited in antiquity – there were only a few areas with sufficient arable lands to support urban populations, namely the small but fertile alluvial plains among the mountains. These areas provided the most favourable setting for ancient habitation. Large parts of the population were concentrated in these sorts of valleys and were organized into small, politically independent settlement units, some of which evolved into autonomous city-states (e.g., Athens, Megara, Thebes, Argos, Sparta).

The deciding conditions for the establishment of a settlement at a particular site were the availability of arable lands and its proximity to the sea. However, other factors were also worth consideration: security, access to water resources, and whether or not the position allowed for the ability to control major communication routes (see, for example, the cases of Corinth in the Corinthian gulf; Eretria and Chalkis in the Euboean gulf).

People on the other side of the Aegean in Asia Minor also sought these environmental conditions for settlement. Large mountain ranges separate the coastline from inner Anatolia, and many ancient settlements are spread along the coast, usually close to estuaries and fertile valleys (e.g., Troy, Smyrna, Ephesus, Miletus, Halicarnassus, Iasos).

The fact that the most important Greek cities are found in the eastern part of mainland Greece is not only related to the formation of the terrain and its proximity to the Aegean Sea˙ the region’s favorable climate was also a factor. The moderate, dry climate prevailing east of the Pindus mountain range suited the cultivation of cereals, legumes, and vegetables. This is in stark contrast with the western portion of the mainland, where increased rainfall makes control of crop production a difficult task.

RESOURCES, ECONOMY AND TRADE

The ancient Greek economy was based on agriculture. However, the overall lack of extensive arable areas never allowed for large-scale production. A mixed system of small-scale farming and commercial enterprise was the only reasonable response to the limitations of the Greek landscape. The Aegean offered access to almost any area of the known world: to the East through Crete, the Dodecanese, and the southern Anatolian coast; to the Black Sea through the islands of Skyros, Lemnos, and the area of Troy; to the West through the Corinthian gulf and the Ionian islands.

Grain shortages were a constant problem for Greek cities and the islands, which they tried to solve with imports from overseas (Thrace, the Black Sea, and even Egypt). Another commodity in short supply for the ancient Greeks was timber. Despite the region’s mountainous terrain, Greece only has a few forests with timber suitable for the construction of buildings and ships. Since the people at the time were heavily dependent on ships for maritime trade and, at the same time, particularly active in constructing monumental temples and other public buildings, Greek cities frequently had to import timber from Asia Minor or the Levant.

Mineral wealth was also fairly limited. Apart from considerable deposits of iron ore, Greece only had a few valuable metal resources: lead-silver ores at Laurion in Attica and Siphnos in the Cyclades, copper sources at Laurion and the island of Kythnos, and rather limited amounts of gold at Mt. Paggaion, Thasos, and other Macedonian and Thracian areas.

These resources were intensively exploited, but the constant need for metals (which were vital for the production of tools and weapons) led to shortages that made imports a necessity.

THE AEGEAN SEA AS A MAJOR ROUTE OF TRADE

Under such conditions, maritime trade provided the basic means for Aegean societies to acquire the resources they needed to survive and thrive. The sea also offered ways out of social and economic crises. During the 8th and 7th centuries BC, for example, an upheaval led to the migration of populations to unoccupied lands overseas, where they established Greek colonies.

The Aegean, with its dry climate and relatively temperate winds, offered ideal conditions for navigation. The more than 500 islands that are scattered across it (with a total perimeter of approximately 7000 km) and the curving coastlines of the surrounding land masses (5000 kilometres in total length) offered plenty of good harbours for the development of coastal navigation from a very early stage in history.

GREEK COLONIES

The establishment of colonies from southern France to the Levantine coast, and the subsequent development of commercial relations with those areas, were of crucial importance.

Already from the 7th c. BC, Greek presence was attested throughout the eastern and central Mediterranean, and from the 5th c. BC onwards, Athens and other Greek cities were among the leading commercial powers in the Mediterranean.

In this way, the Greeks managed to ensure a constant flow of goods that were necessary for the development of an effective economy.

At the same time, they came into contact with the majority of cultures across the ancient world. By adopting new ideas and stimuli from such encounters, they created a civilisation renowned for its wealth, originality, and expressive power. The role of the sea in that process was incredibly important.