The archaeology of the Cyclades

CYCLADIC ART

HUMAN PRESENCE IN THE CYCLADES

The Cyclades have been continuously inhabited (nearly without interruption) since around the 5th millennium BC. Even earlier than that, the first traces of human activity in the Cyclades date to the 7th millennium BC – this evidence comes from the island of Melos, which seems to have been visited by people from mainland Greece who were in search of high-quality obsidian. This hard volcanic rock was extensively used throughout the Aegean, primarily in the Neolithic period but also during the Bronze Age, for the manufacture of cutting tools and weapons.

Permanent settlements were established in the Late Neolithic period (c. 5000 BC) on Andros, Naxos, Antiparos, Amorgos, Thera, and a few more islands. Those early settlements were small in size and their inhabitants depended on agriculture, animal-breeding, and fishing to survive. Subsequently, in the Early Cycladic period (3200 – 2000 BC), all of the Cycladic islands were inhabited and had started developing relationships among themselves, as well as with the settlements of the surrounding Aegean coasts. Since that time, occupation has continued nearly uninterrupted.

EARLY BRONZE AGE

Towards the end of the fourth millennium BC, some significant cultural and social changes took place in the Aegean, signaling the end of the Neolithic way of life.

The most important development was undoubtedly the introduction of metallurgy from the Near East. The use of metals substantially improved the selection of tools for all activities (farming, tree-felling, architecture, shipbuilding, etc.) and also enabled the production of bronze weapons, which, due to their greater effectiveness, significantly altered the nature of warfare.

Other changes observed during this period include the introduction of new crops, such as the olive tree and the grapevine, the rapid increase of maritime contacts, and the widening of trade networks.

Improved living conditions led to population growth, which we see as early as 2700 – 2500 BC with the emergence of proto-urban settlements (Poliochni, Thermi, Troy, Manika, Aigina, Lerna). A number of these settlements, notably Troy and Poliochni, were established at strategic points, which placed them at an ideal position for controlling important sea routes. They were also fortified with mighty walls, perhaps in response to emerging conflicts over access to metal sources and trade networks.

The importance of bronze as a symbol of wealth and status, as well as the growth of trade and craft specialization, contributed to what archaeologists have interpreted as a more complex (i.e., hierarchical) social system. This manner of social differentiation is particularly visible in the burial practices on Crete and the Greek mainland, where we see that some ancient peoples would construct large tombs for multiple burials and sometimes bury their dead with extravagant goods.

Within this environment and at about the same time, four distinct “cultures” developed in the Aegean region: the Early Minoan culture on Crete, the Early Helladic culture on the Greek Mainland, the Early Cycladic culture on the islands of the Cyclades, and the Early Bronze Age culture on the Northeast Aegean islands, which was strongly influenced by the coastal regions of Asia Minor. The Cyclades, thanks to their strategic position in the central Aegean and their abundant mineral resources (marble, obsidian, etc.), enjoyed a privileged role in trade and became a melting pot of diverse cultural influences.

Around 2300 BC, there were several upheavals throughout the Aegean––though Crete seems to have been spared at that time. Several settlements were abandoned, others were hastily fortified, and maritime trade diminished. Moreover, the appearance of new burial habits, as well as new architectural and pottery types, has been interpreted by some researchers as suggesting the arrival of new population groups in the Aegean region.

The reasons for these disturbances are not clear, but they may be associated with conflicts over access to copper and tin (essential for the production of bronze, which is more durable than either on their own), new methods of warfare (due to the use of these more durable metal weapons), and social pressure caused by the increase in population and the concentration of large numbers of people in urban centers. Whatever the reasons, during the final phase of the period (Early Cycladic III, 2300 – 2000 BC), the character of Early Cycladic culture changed. At the same time, arts such as marble sculpting began to decline, disappearing altogether by the end of the 3rd millennium BC.

EARLY CYCLADIC I (3200 – 2800 BC)

Information regarding the Early Cycladic I period comes almost exclusively from cemeteries. Settlement remains are scarce, perhaps because perishable materials were still being used as building materials. In contrast, the large number of cemeteries suggests an increase in corresponding habitation sites and thus, an increase in population.

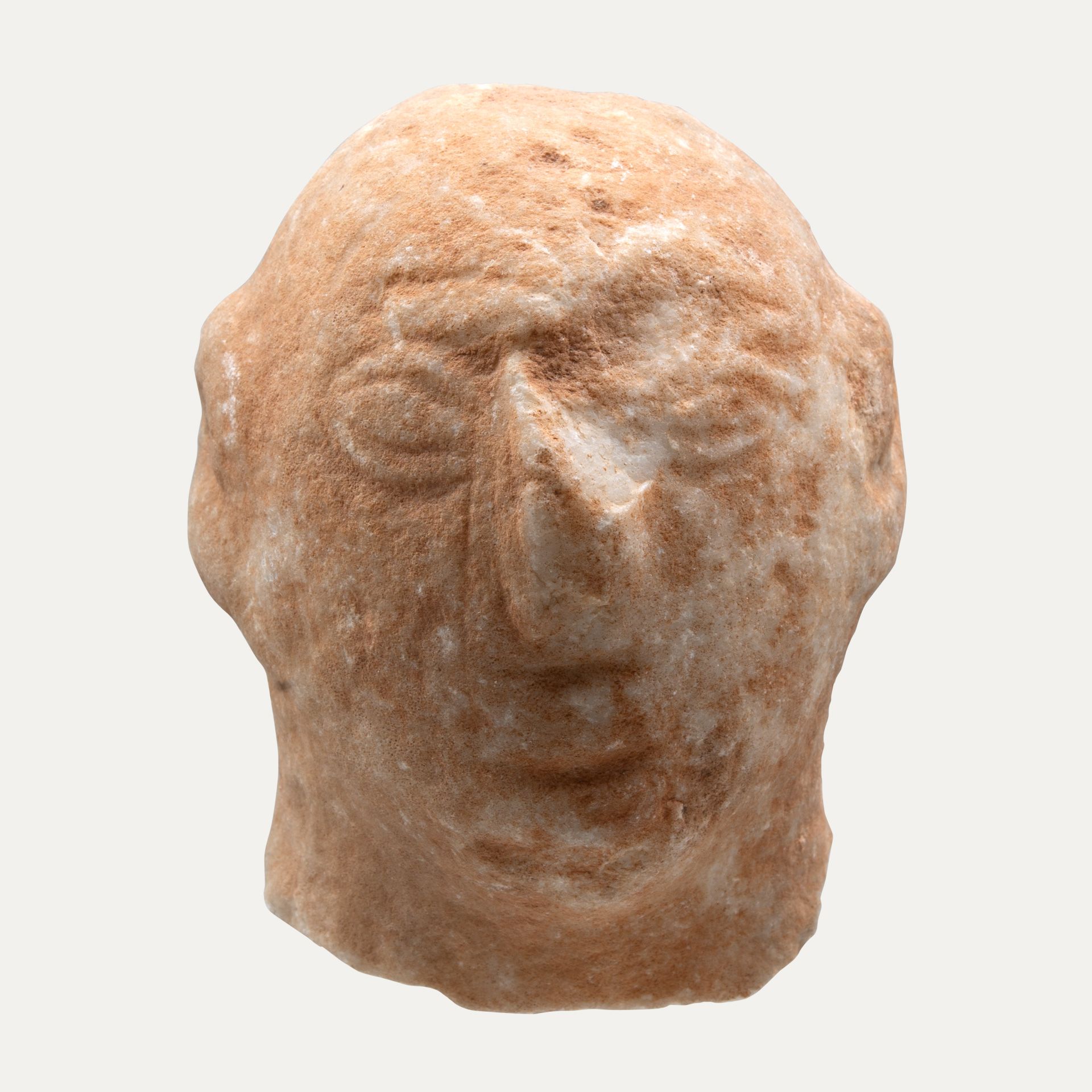

During this period, burials were made in simple cist-graves, and pottery was usually decorated using incision. Also in this period, the craft of carving marble started to develop, and the first marble vessels (kandiles, bowls, etc.), schematic figurines (violin-shaped, spade-shaped), and naturalistic figurines (Plastiras type) appeared. Metallurgy was introduced in the Cyclades, but the everyday use of metals – mainly copper – was still limited. What’s more, the Cyclades saw little contact (for trade or otherwise) with other areas in the Aegean.

EARLY CYCLADIC II (2700 – 2400/2300 BC)

The Early Cycladic II period was the height of Cycladic culture. Existing settlements expanded and new ones were established in previously unoccupied areas, a trend paralleled in Mainland Greece (Early Helladic II period) and in Crete (Early Minoan II period) at the same time. Also, a new type of earth-cut grave with a lateral entrance was introduced in the Cyclades, which was meant to be used for multiple burials.

During the transitional phase from the Early Cycladic I to the Early Cycladic II period, the famous “frying-pans” appeared in the archaeological record. Around 2500 BC, new shapes dominated in the ceramic repertoire, with a notable example being sauce-boats. At the same time, significant advancements were made in metallurgy with the manufacture of the first bronze weapons (daggers, spear-heads) and tools.

However, the most characteristic feature of the period was the impressive development of marble carving. During this period, Cycladic sculptors skillfully produced a huge number of abstract and highly standardized female figurines, as well as a number of elaborate vessels. At the same time, contacts with Mainland Greece, Crete, and the north and northeast Aegean increased considerably.

EARLY CYCLADIC III (2300 – 2000 BC)

During the Early Cycladic III period, major changes took place in the Cyclades, the most noticeable being the abandonment of many settlements and traditional burial sites, along with the construction of fortification walls in several of the surviving settlements. Similar changes have been observed in Mainland Greece and the Anatolian coast at the beginning of this period, possibly reflecting a widespread phenomenon of unrest and instability all over the Aegean.

Some scholars interpret these disturbances as the result of migrations and the arrival of new populations in the Aegean. They stress the appearance of new types of pottery and metal artifacts, which seems to have originated in Asia Minor. In the course of this troubled period, the art of marble carving in the Cyclades began to decline, and ultimately died out at the end of the 3rd millennium BC.