Pottery and vase – painting of the archaic period

ANCIENT GREEK ART

ARTS AND SCIENCE

The Archaic period (700 – 490/480 BC) represents a formative stage of Greek art. The pronounced oriental influences, particularly in vase-painting, metalwork, and sculpture (“Orientalizing” period) are characteristic of the 7th c. BC.

These influences were imaginatively adopted by Greek artists, who, during the 6th c. BC, created distinctive local idioms that led to the mastery of proportion and the realistic rendering of the human figure. In the same period, the basic architectural orders were established (Doric and Ionic), the form of the peripteral temples was finalized, and the art of architectural sculpture was refined.

The changes that took place in the 6th c. BC, as well as the tyrants’ many favourable policies towards the arts, led to the growth of philosophy, the natural sciences, and literature in mainland Greece and Ionia. At the same time, the theatrical art of drama was born in Attica – with direct association to the Dionysiac cults.

During the Archaic period, besides the other changes and evolutions, the two most well-known vase-painting techniques were born: first, the black-figure and, then, the red-figure.

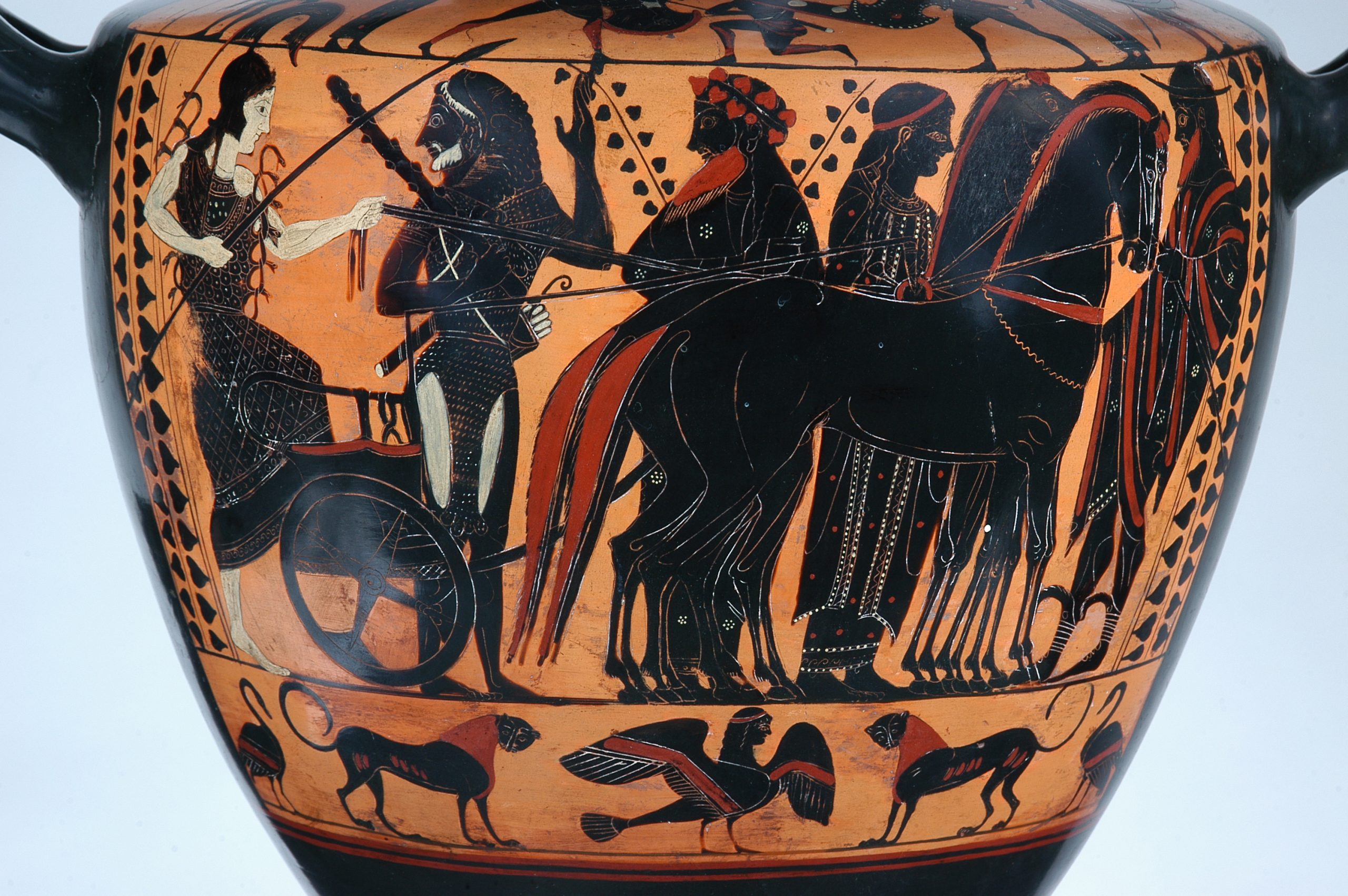

BLACK-FIGURE VASES

The black-figure technique was a common style of decoration in ancient Greek vases; it depicted figures in black silhouette against a bright orange background. The figures’ outline and details (facial and anatomical features, garments, etc.) were rendered by incision.

Overall, black-figure was the predominant style of decoration used throughout the Archaic period.

Neither the lustrous black of the figures nor the bright orange of the background was achieved through the use of actual pigments: rather, potters managed to produce such an impressive contrasting effect by employing a sophisticated technique of surface treatment and firing. Initially, the whole surface of the vase was coated with a slip of fine clay. On this first layer, figures and other decorative motifs were drawn by incision and covered with a slip of finer clay mixed with small quantities of alkaline minerals (e.g. potash).

Then, the vase was fired in temperatures exceeding 800°C. The firing process had at least three distinct stages, during which the potter controlled the supply of oxygen through the vents of the kiln. The successive exposure of the vase to oxidation (with oxygen) and reduction (without oxygen) resulted in the vitrification of the mineral-rich gloss, while the rest of the surface retained the orange-red colour of the clay. Incised details also retained the orange colour, therefore producing sharp contrasts in the interior of the figures. In many cases, vase-painters added white, red, or purple pigments in order to emphasize specific details (white, for example, was used – among others – for female figures).

The invention of the black-figure technique

The black-figure technique was invented in the city of Corinth at the beginning of the 7th c. BC. Corinthian vase-painters used the new style to depict animals, imaginary creatures (e.g. sphinxes), plant motifs, and – only occasionally – human figures. Since most Corinthian vase-types were of a small size (aryballos, alabastron, olpe), local potters mastered the skills of accurate design and the careful application of the slip and gloss. The technique was introduced in Attica at about 630 BC and became swiftly popular among vase-painters – especially those working in the famous Kerameikos quarter of Athens. Athenian artists were particularly interested in depicting human figures in action, and they soon started producing narrative compositions of extraordinary quality. By doing so, Athenian artists introduced a major change in the production of painted pottery.

Instead of serving as a decorative element meant to enhance the aesthetic quality of a pot, vase-painting became an effective medium for visualizing scenes from mythology, history, worship, everyday life, etc. From then on, pottery was a form of visual art, a new means of communication and education, and a powerful vehicle for ideological and political propaganda. Black-figure vases contain the largest corpus of mythological scenes in ancient Greek art, and some of them had clear political and ideological connotations. Attica produced black-figure vases of the highest quality – quickly displacing Corinthian products – and won the markets of the Mediterranean. The black-figure technique continued to spread and was used throughout the Greek world. Other important production centres included: Boeotia, Laconia, Euboea, some Ionian cities, and the major colonies of southern Italy and Sicily.

The great masters of black-figure vase-painting

Sometimes, potters and vase-painters incised their names on the surface of their vases. The earliest painter’s signature is that of Sophilos on a black-figure dinos (a vessel for mixing wine with water) depicting burial games of Patroclus.

We know the actual names of a dozen vase-painters from such inscriptions. However, the typological study of black-figure vases suggests that hundreds of different “artists” or “workshops” existed and were conventionally named after the city which hosts their most important creations – or after characteristic features of their style (e.g. The Heidelberg Painter, the Gorgon Painter, etc.).

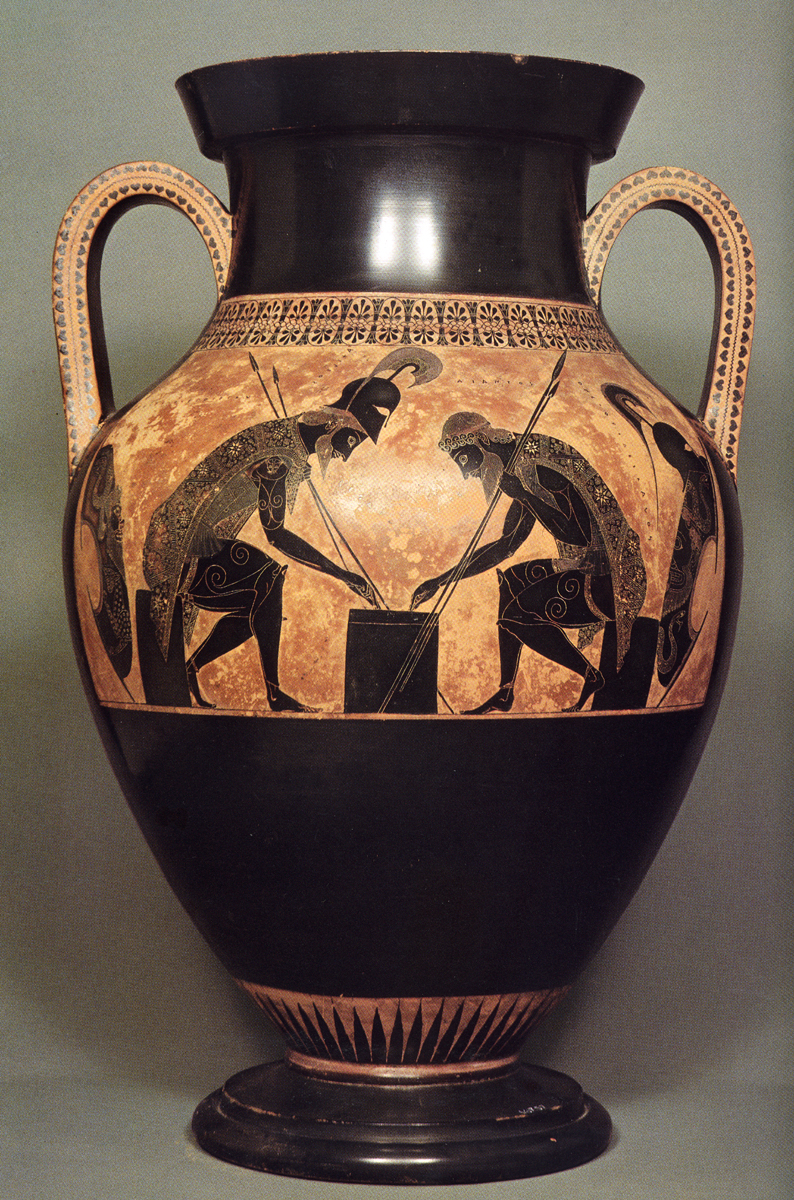

It is easy to single out prominent individuals, such as Lydos, Amasis, and Exekias, among the many important artists who used the black-figure technique. Exekias even managed to enhance the plasticity and expressiveness of the figures, creating unmatched compositions of a dramatic power that clearly foreshadowed Classical art.

Exekias, who lived and worked in the second half of the 6th c. BC, brought the black-figure technique to its limits. In around 530 BC, however, Athenian potters invented the red-figure technique, which offered more freedom to vase-painters and soon became the predominant style in Attic decorated pottery. The black-figure technique was abandoned by the middle of the 5th c. BC. However, some vases of special ritualistic use, such as Panathenaic amphoras – the prize for the winners of the Panathenaic Games – continued to be made in the traditional black-figure technique for a long time.

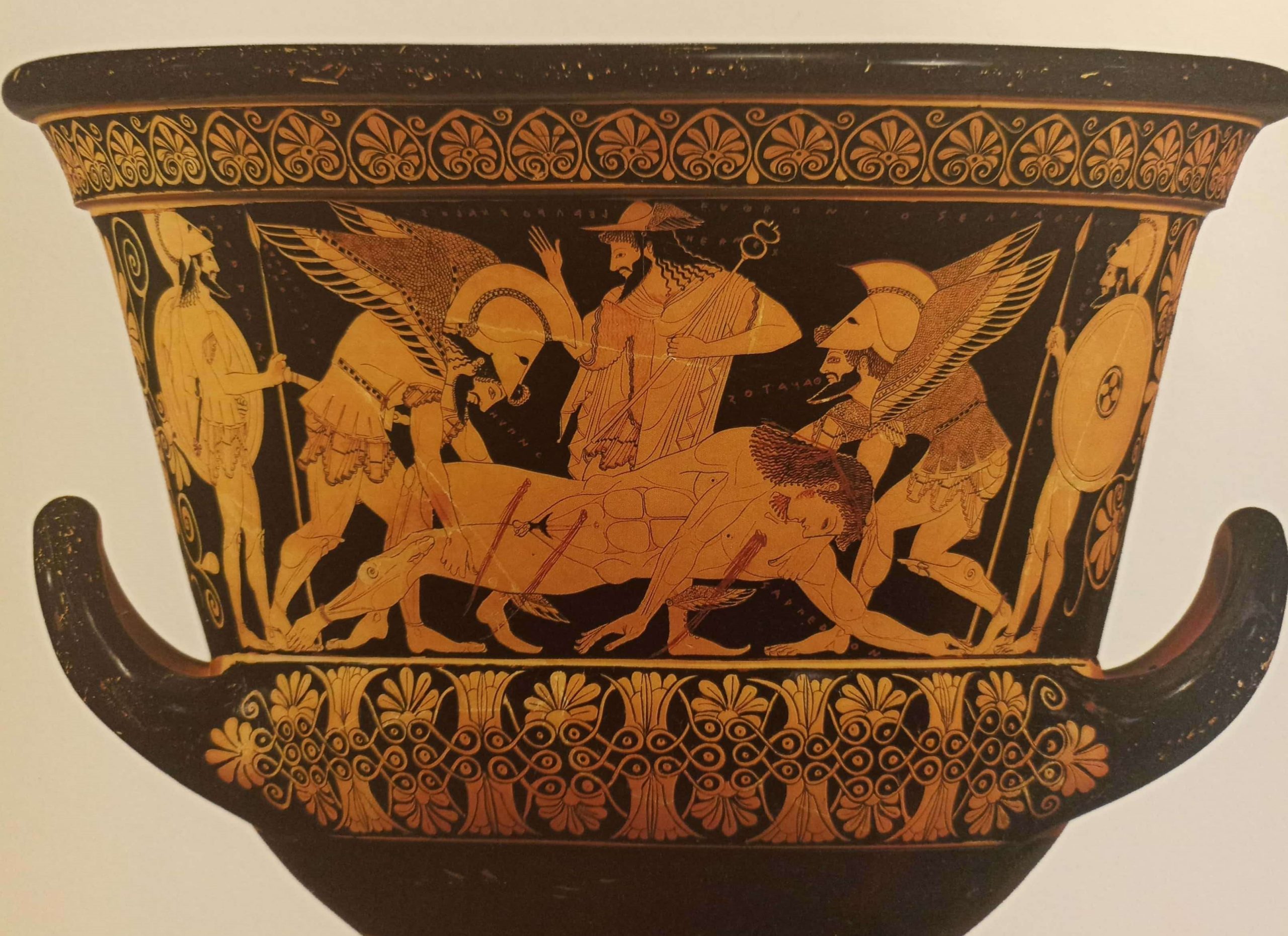

RED-FIGURE VASES

Red-figure technique was the primary decorative style for vases in the Classical period. In fact, it was a reversal of the black-figure technique, as figures were left the colour of the clay while the rest of the surface was coated with a black slip (a layer of fine-grained ferrous clay).

The black slip was then vitrified when fired, therefore obtaining its characteristic glossy appearance. The figures’ outline and details (facial features, dress folds, etc.) were rendered in more diluted brown glaze, which also darkened during firing.

In this technique, painters had first to draw the figures on the vase with charcoal (or another material, which usually was not preserved after firing). This was necessary to ensure that the image of the figures would not be covered over when the surface was coated with black slip.

Undoubtedly, red-figure was a more demanding technique than black-figure, but it was also more rewarding, as it produced brighter figures that were able to stand out more prominently against the dark background. The technique also allowed for a more detailed treatment of human anatomy and dress and offered greater potential to represent the three-dimensional space.

Red-figure vase-painting is closely associated with Attica, which was the most prolific centre of production and distribution of such vases. Nevertheless, important examples were also produced in southern Italy, especially after 400 BC, when Athenian trade declined sharply and local workshops were left free to develop their own artistic idioms. Red-figure vases were also created by workshops in Corinth, Boeotia, Arcadia, Laconia, Euboea, Crete, etc.; though these were primarily for local consumption rather than export.

The great masters of the red-figure vase-painting

The red-figure technique was the result of experimentation conducted in the workshops of Kerameikos, Athens – when the limitations of the black-figure technique had become evident. The earliest red-figure vases date to 530 BC and are attributed to the “Andokides Painter”, whose real name is not known but was probably a pupil in Exekias’ workshop. The transition between the two styles was not abrupt, as the production of black-figure vases went on for decades after the new invention. In fact, some early vases were “bilingual”, with black-figure decoration on one side and red-figure on the other.

Red-figure vases quickly became a product of high-demand and were widely exported mainly to Italy. They continued to be very popular until the second half of the 4th c. BC. The earliest stages of the red-figure technique fall within the late Archaic tradition. Among the numerous early red-figure painters, one could distinguish Euphronios, Euthymides, Phintias, Smikros, the Kleophrades Painter, and the famous Berlin Painter – who created scenes full of vigour with imposing figures – often unframed – that claim more space on vase decoration than usual.