Greek colonization

ANCIENT GREEK ART

THE “FIRST COLONISATION MOVEMENT”

Population movements were common in antiquity, and large-scale migrations occurred all over the eastern Mediterranean since the end of the Late Bronze Age. According to ancient traditions, it was then – at the end of the Late Bronze Age – that Dorian tribes arrived in central Greece, the Peloponnese, and the Aegean islands. In the 11th c. BC, the so-called “first colonisation movement” began, and the Ionians and Aeolians migrated to the islands of eastern Aegean and to the coasts of Asia Minor.

The migration was most likely due to displacements caused by the aforementioned “Dorian invasion” – and therefore probably had an urgent and non-systematic character.

THE “SECOND COLONISATION MOVEMENT”

Between the 8th and the 6th c. BC, the Greeks, from both the mainland and the islands, migrated in large numbers to the south of Italy and Sicily and, later, to areas even further west, as well as to the east and the Black Sea, in order to found new cities (colonies). This phenomenon, commonly known as Greek Colonisation (or the “second colonisation”), resulted in the dissemination of Greek culture throughout the Mediterranean. The second colonisation movement was much more organized, involving specific parts of the population and was supervised by the authorities of each city. After receiving a divination – usually from the oracle of Delphi – a member of the aristocratic class was selected to act as the “founder” of a new colony and was responsible for the organisation of the colony, the distribution of land, the establishment of laws, and the erection of temples dedicated to the same deities that were worshipped in the mother-city. Participation in the expedition was not necessarily voluntary, and expeditions may have included people from other areas too. Women were usually excluded, and settlers took spouses from the local population.

The “second colonisation movement” can be divided into two broad phases. The first one, which lasted from around 775 BC to the early 7th c. BC, mainly included Euboean cities (and, to a lesser extent, Megara, Corinth, and a few more centres) that sent colonial expeditions to the south of Italy and Sicily. Some of the most important Greek colonies were founded in this period, including Catania, Leontinoi, Zangle, Megara Hyblaea, Syracuse, Sybaris, Croton, Taras, etc.

In the second phase, which lasted from the early 7th to the late 6th c. BC, the number of cities participating in the colonisation movement increased considerably, and destinations became more varied. Greeks from both sides of the Aegean (and the islands) migrated to the west – as far as the coasts of modern France and Spain, and also to Thrace, the Propontis, the Black Sea, and the North African coast. Sicily and southern Italy continued to host the largest concentration of Greek colonies, and the Greek part of the Italian peninsula was soon named “Magna Graecia”.

THE CAUSES

The reasons for such an extensive migration movement seem to be rather complex, though social and demographic pressures were certainly of crucial importance. During the later parts of the Geometric period, the population in Greece increased considerably, and, by the 8th c. BC, the constant split of agricultural lands by descendants had created shortage of resources. Large sectors of society lived in poverty, and migration, though desperate, was a viable solution. (Herodotus reports that the colony of Cyrene, in modern-day Libya, was founded by the inhabitants of Thera after a famine had struck the island). For that reason, Greek colonies were usually established on previously uninhabited areas and in close proximity to good arable land.

Additionally, the expansion of trade networks and the search for new resources (mainly metals) was clearly another driving force behind the migration movements. Pithekoussai in Italy, Naukratis in Egypt, Emporion in Spain, and several other colonies had an exclusively (or mainly) commercial character, and the colonists exploited local metal resources in both the West and the Black Sea – where large deposits of gold and silver were available.

Sometimes, however, political problems were the driving force behind the founding of new colonies, as was certainly the case with Taras in southern Italy; a city that was established by Spartans who had been expelled from their mother-city during the first Messenian War.

THE COLONIES AND THEIR CULTURE

The kind of relationship that was established between the Greek settlers and the indigenous populations is not known – apart from few exceptions. In Sicily, it seems that local inhabitants were rather friendly to the Greeks – as the wide adoption of Greek culture on the island suggests.

On the other hand, the indigenous tribes of southern Italy were more reluctant to assimilate to Greek customs, despite the fact that Etruscan art was evidently influenced by Greek styles. Also, the fact that many ancient Greek myths set some of the most turbulent adventures to the west of the Greek world – as done in the Odyssey, for example – may reflect the difficulties confronted by the first Greek colonists.

In terms of political organization, the colonies were structured as city-states; however, power rarely escaped from the strict control of the aristocracy, which controlled the economy, trade, and legislation – leaving little space for political efforts made by other social groups. Additionally, the aristocratic regimes persisted for a long time because the middle class – the main agent of political change in Archaic Greece – was very restricted in the colonies. Therefore, the only social upheavals were implemented by influential individuals who wished to accumulate power and reign as tyrants. Finally, relations among the new city-states were not always harmonious, and adversities and even military conflicts were not uncommon.

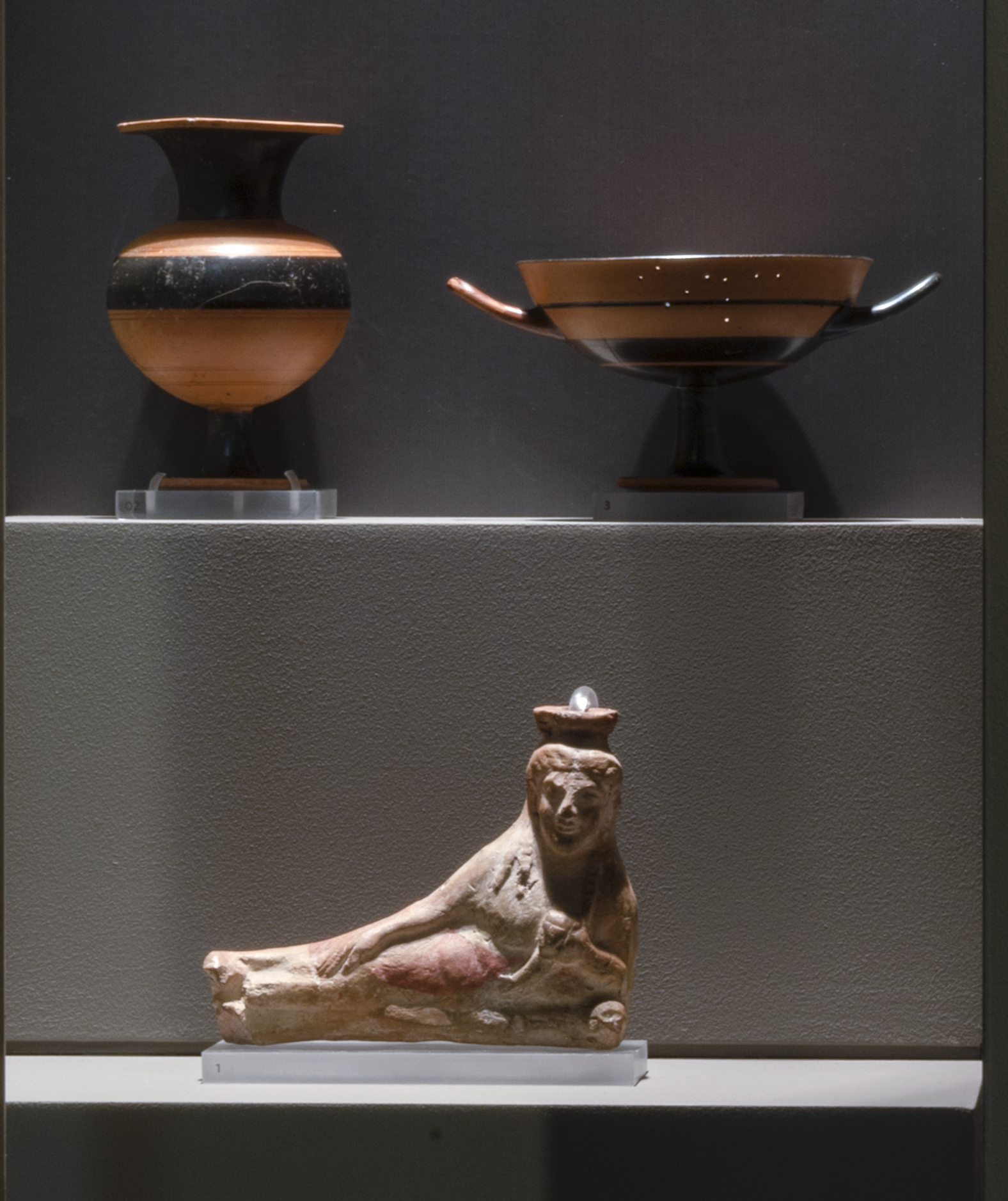

The colonies, especially those in Magna Graecia, actively supported Arts and Letters. Prominent intellectuals – such as the philosopher Pythagoras (Croton) and the mathematician Archimedes (Syracuse) – lived and worked in Magna Graecia. Impressive Doric temples were built in the cities of southern Italy and Sicily, and exquisite marble and bronze statues were offered to the local sanctuaries. Vase-painting closely followed developments made in Greece and flourished during the Classical (490/480 – 323 BC) and the Hellenistic periods (323 – 31 BC). Coinage, too, evolved into an elegant form of art.

Cultural and artistic developments were the result of the prosperity generated by (mainly) trade. On the Italic peninsula, however, this would eventually bring the Greeks into conflict with other trading powers, such as the Phoenicians, the Carthagenians, and, finally, the Romans. The Roman conquest in the middle of the 2nd c. BC ended the independence of the Greek city-states in southern Italy and Sicily. A similar fate awaited the rest of Greek colonies in the following decades, as the Romans advanced eastwards, occupying territories that were incorporated into the newborn Roman Empire in 31 BC.