From cycladic culture to modern art

CYCLADIC ART

IN THE QUEST OF PRIMITIVE

By the last quarter of the 19th century, artists began to explore the creations of earlier or so-called ‘primitive’ civilizations, which were shown in several museums and ethnological collections around the world.

There was also a growing interest in the essence of things; many artists wanted to return to the origins of creative possibilities and therefore experimented with eliminations, reductions, abstraction, and refinements.

THE “PIONEERS”

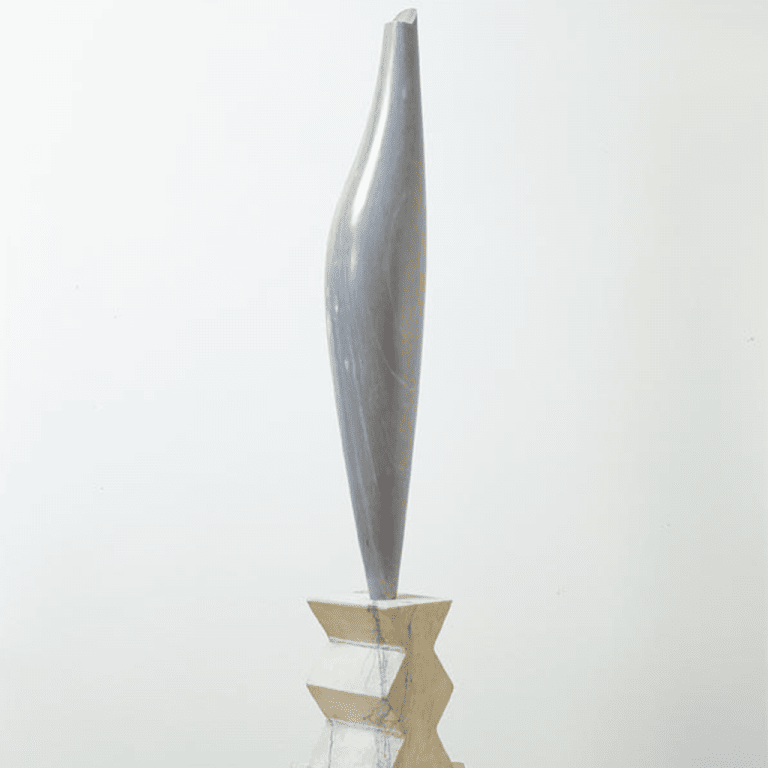

Brancusi was one of the first artists who tried to unburden western art of its excessive decorative elements and make us conscious of shape. In fact, as sculptor J. Epstein observed, Brancusi sought from the very beginning to express essential and archetypal elements, namely features that are recognizable in ancient civilizations.

Works like his many variations of ‘Bird,’ the ‘Fish’ series, the ‘Female head,’ or his work ‘The Beginning of the World’ (inspired, according to Henry Moore, by a large Cycladic head in the Louvre), became symbols of the idea that they represented – as is the case in Cycladic art – and were not specific representations of individual objects.

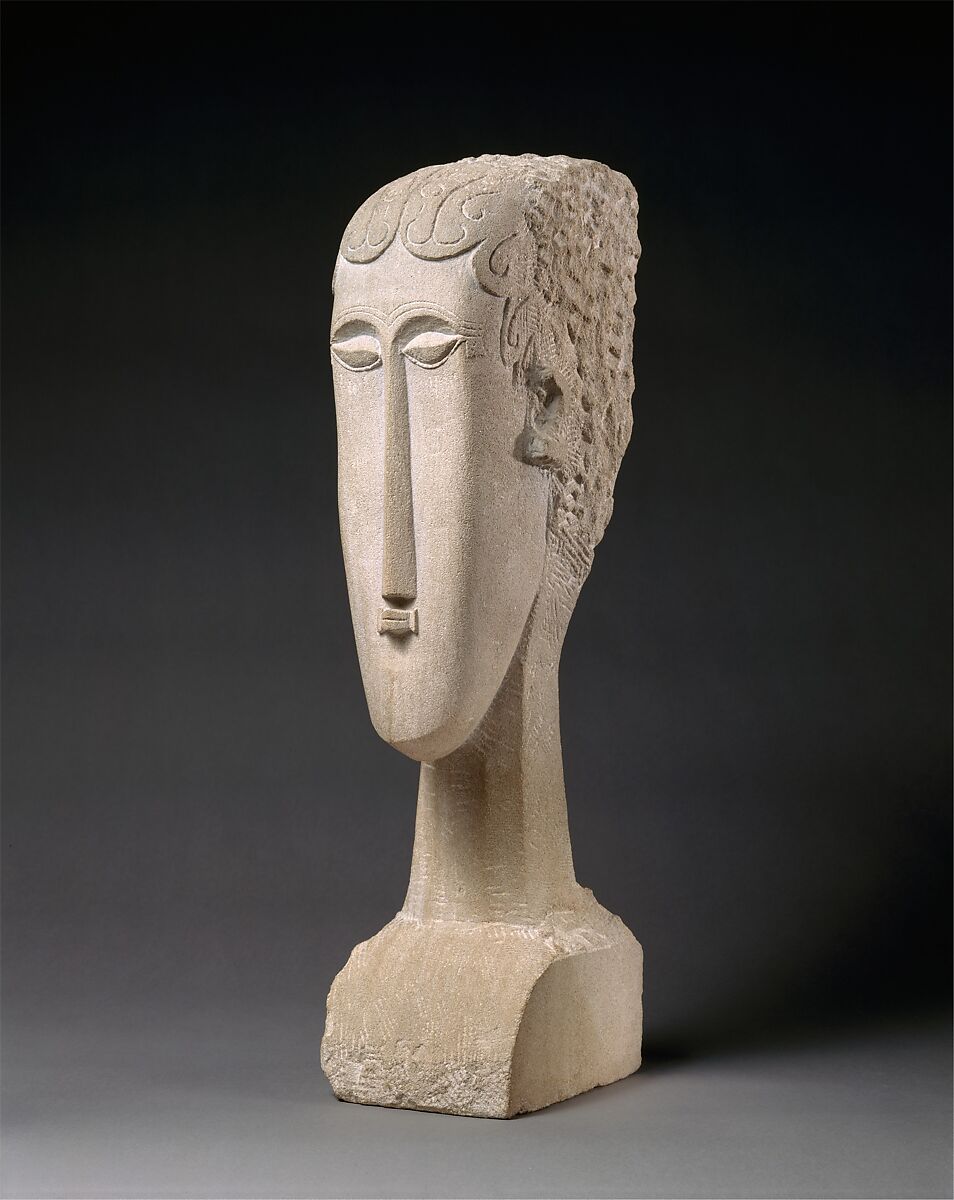

Following a similar path of research regarding essentialism and experimentation, sculptors like Epstein, Derain, and Modigliani, were each attracted to the stark power of the inexpressive, immobile heads from ancient civilizations.

They were equally drawn by the ‘universal reference to humanity’, stripped of all individuality, and so were abandoning the prevailing academic formalities and preference for realistic representations of artistic subjects.

CYCLADIC ART AND THE MODERNISTS

Elements such as simplicity, abstraction, harmony, vitality, and staying true to the material – which characterize Cycladic art – were some of the tendencies exploited by early 20th century artists. Archetypal shapes like the oval or ovoid, commonly seen in Cycladic art, also became common forms in modern art.

Visual similarities between Cycladic art – in particular the schematic figurines – and 20th century art can be detected in the works of Hans Arp, Alberto Giacometti (considered to be deeply influenced by the hieratic structure of Cycladic art), Ben Nicholson, and Archipenko (in terms of the flatness of his sculptures).

Similarities can also be found in the works of Henry Moore, whose anthropocentric sculptures were directly influenced by Cycladic art, and Barbara Hepworth, one of the first artists to use color for the details in her sculptures – also an element known to have been applied in Cycladic sculpture.

Another less stressed but equally important commonality between these artists was their choice to use marble, the material with which the Cycladic craftsmen experimented and created unique and never-before-seen forms. The modernists’ preoccupation with so-called ‘primitive’ or ‘archaic’ cultures had a tremendous impact on thought and aesthetics in the western world, which was freed from the limits of representational art and turned its gaze towards abstraction, symbolism, and other major currents of the 20th century.

At the same time, it completely changed the public’s appreciation for so-called ‘primitive’ art. Under the influence of Brancusi and other artists, Cycladic figurines and other artifacts from prehistoric cultures, previously seen as ‘ugly’, ‘vulgar’, or even ‘barbaric’, became objects of admiration and symbols of human values and shared origins. This development, however, also had negative consequences: the great demand for such artifacts by museums and collectors raised their price in the international art markets, fueling an explosion in the illicit trafficking of antiquities.