Hygieia. Health, Illness and Treatment from Homer to Galen

ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXHIBITION

NOVEMBER 19, 2014 UNTIL MAY 31, 2015

THE EXHIBITION

From the dawn of its existence, humanity has strived to improve all aspects of living conditions. Achieving and maintaining good health, seeking to understand the causes of diseases and, mainly, searching for solutions to fight and treat illnesses have been a primary concern and interest throughout all periods of civilization.

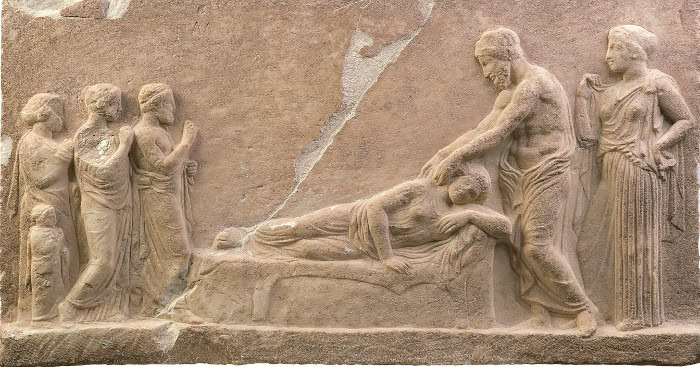

The Museum of Cycladic Art presents the major archaeological exhibition Hygieia: Health, Illness and Treatment from Homer to Galen, focusing on the universal subject of Health, providing an overview of the evolution of ancient medical practices: the transition from magico-religious healing practices to rational, scientific medicine. The exhibition presents approximately 300 artifacts with the participation of 41 international museums, including the Louvre, the British Museum, the National Archaeological Museum of Athens, the Musei Capitolini. Our earliest literary sources for the history of Greek medicine are the epic works of Homer which clearly reveal that the Greeks of the Heroic Age linked sickness and disease with the supernatural, regarding them as manifestations of the wrath of the gods. To appease the gods, they employed prayers, purifications, animal sacrifices etc. Even the idea of health (Hygieia) was personified as a wonderful goddess usually accompanied by a snake, the symbol of therapy.

By the late 6th century BC, however, philosophy came to exercise a powerful influence upon the development of medicine. Hippocrates and the classical Greeks were the first to evolve rational systems of medicine free from magical and religious elements, realizing that maintaining good health and fighting disease depend on natural causes.

VIDEO

INSTALLATION SHOTS

HEALTH – HYGIENE

Health is a timeless, universal benefit. In the Platonic dialogue Gorgias, Socrates quotes a drinking song of the 6th or 5th c. BC, according to which health is the greatest good a man can have (“ὑγιαίνειν μὲν ἄριστόν ἐστιν”). Other goods enumerated in this song are “to have become beautiful, and third is to be wealthy without fraud”. According to the poet Menander (4th c. BC), “there is nothing better in life than good health” (“οὐκ ἔσθ’ ὑγιείας κρεῖττον οὐδέν ἐν βίῳ”).

Hippocratic physicians emphasized the importance of diet in maintaining health as well as in treating disease. In antiquity, the word diet was not limited strictly to food (no. 1), as it is nowadays; it expressed a broader concept, which also encompassed – and always in moderation – drink, physical exercise, baths, massages, sleep, sexuality, and a person’s habits and way of life in general. Moreover, the ancient Greek verb diaitomai, the source of the word diet, means to live in a specific way.

Equally important to protecting health was cleanliness on an individual level, as well as on the level of the broader social group, the city. Public health was a concern from as early as the prehistoric period, as evidenced by the amenities in the Minoan palaces of Crete: they had very good lighting and ventilation, aqueducts with terracotta pipes, sewer systems, baths, and other sanitary facilities.

Ancient references to healthy living – the Hippocratic treatises On Airs, Waters, and Places and On Regimen, for example, which emphasize how much the natural environment and general lifestyle influence health – are corroborated in this section by various archaeological finds, such as: vases with scenes of personal hygiene that depict not only men washing in fountain structures but also prostitutes ensuring the cleanliness of their well-used bodies.

ILLNESS

According to Plutarch (1st c. AD), “health is a precious enjoyment, but easily impaired” (“ὑγίεια δὲ τίμιον μέν, ἀλλ’ εὐμετάστατον”), while according to Lucian (2nd c. AD), “there is no benefit in possessing every good if health is absent” (“οὐδὲν ὄφελος τῶν ἁπάντων ἀγαθῶν ἔστ’, ἄν τό ὑγιαίνειν ἀπῇ”).

Originally, prevalent belief had it that the gods inflicted illnesses upon humans as a punishment for impious acts. And since the cure of every illness was similarly godsent, people tried to appease the gods with prayers, magnificent sacrifices, and purifications.

Centuries would pass before the divine provenance of disease was challenged and treatment dissociated from divine intervention. This occurred with the teachings of the Pre-Socratic philosophers (6th c. BC), which served as the foundation for rational scientific medicine.

We derive information regarding the various illnesses people faced in antiquity from ancient medical treatises – primarily the 60 works of the Hippocratic Corpus – that accurately record a host of illnesses. The ancient names of many diseases have survived in modern medicine; these include diabetes, cholera, epilepsy, leprosy, elephantiasis, and others. These treatises also mention a number of epidemics, including the Plague of Athens.

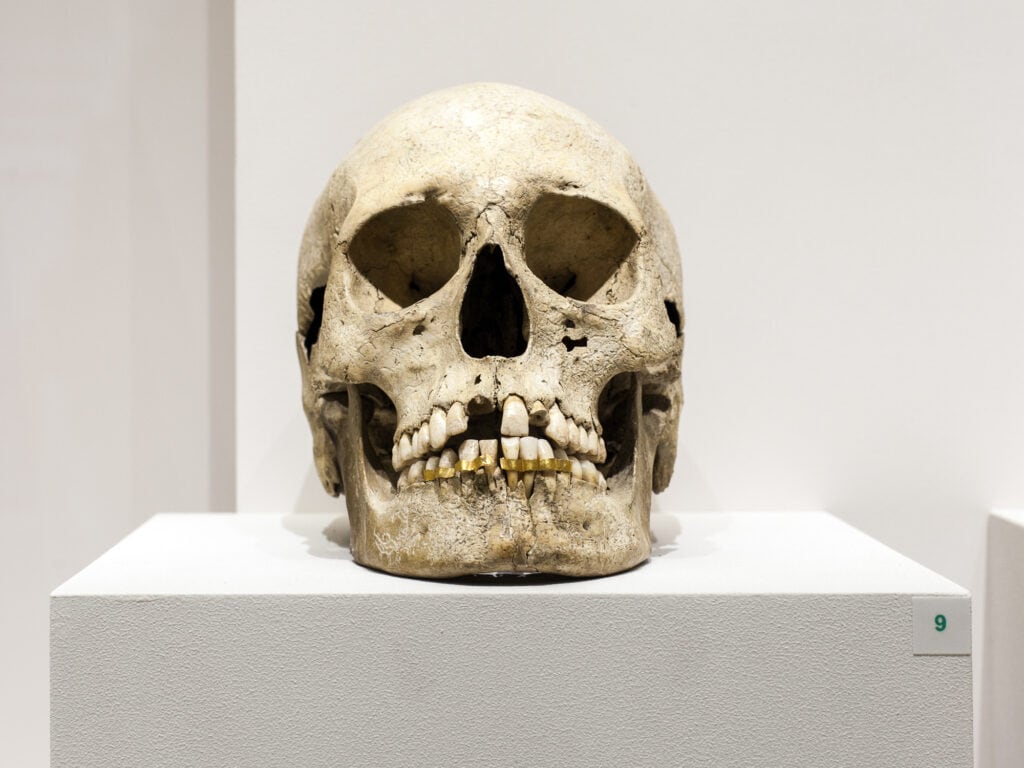

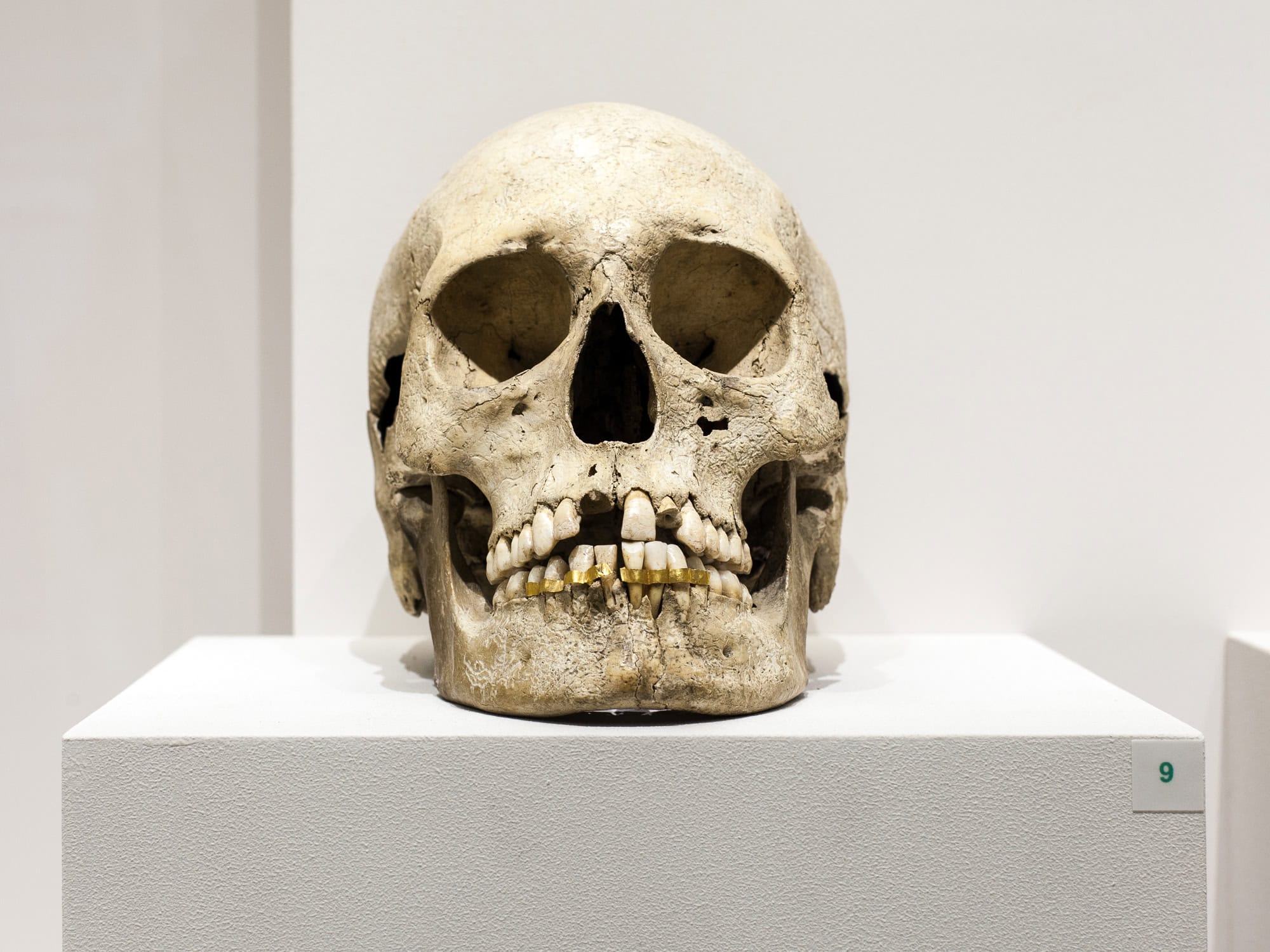

We also collect important information from palaeopathological research conducted on skeletal material found during excavations. This information concerns not only our ancestors’ diet – as manifested in their teeth and bones – but also reveals arthritis, bone tuberculosis, malaria, Mediterranean anaemia, hereditary diseases, as well as various healed injuries.

TREATMENT / HOMERIC MEDICINE

The earliest written testimony available to us regarding the healing practices prevalent in Greek antiquity comes from the Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey. Although their composition dates to the first half of the 7th c. BC, they primarily describe the Mycenaean civilization of the Late Bronze Age – specifically, the period of the Mycenaean King Agamemnon and of the Trojan War, around 1200 BC – as well as the civilization of the Geometric period (11th – 8th c. BC).

There is no pictorial evidence of prehistoric Aegean medical practices, yet finds from the palace archives of the 13th / 12th c. BC permit us to conclude that an established class of people specializing in the healing art existed during that period. Two clay tablets written in Linear B (nos. 1 and 2), which were found in the palace archive of Pylos, contain the words i-ja-te (i.e., ἰητήρ = physician) and pa-ma-ko, (i.e., medicament). This, most likely, is a record of medicaments or medical supplies made for the palace physician.

The study of additional tablets identified various aromatic plants (fennel, cumin, celery, cardamom, coriander, spearmint, iris, and others) that also have therapeutic qualities. It appears the healers of the heroic age turned to the large and rich pharmacy of nature to procure the materials required for preparing their medicines.

TREATMENT / THEURGIC MEDICINE

According to the prevailing theocratic mindset, diseases were sent by the gods and they alone could cure them. Thus, people would resort for salvation to various gods who possessed healing properties, such as Apollo, Zeus, Dionysos, Athena, Artemis, Aphrodite, and others. Healing powers were also attributed to various heroes such as Herakles Alexikakos, Amynos, the Hero-Physician, Syrangos in Piraeus, and, in particular, the seer Amphiaraos, worshipped at Oropos and Rhamnous.

It was Asklepios, however, who emerged as the foremost healing god. Homer refers to him as a mortal, as the king of Trikke in Thessaly and a peerless physician. In later myths and traditions he is referred to as a demigod, the son of Apollo and the mortal Koronis, possessed of the unique ability to grant health. Around the middle of the 5th c. BC, Asklepios was elevated to the rank of the gods. The popularity of his cult surpassed all others and endured even past the advent of Christianity until approximately 500 AD.

Asklepios was frequently accompanied by members of his family: his wife Epione (= comforter of pains), his two sons Machaon and Podaleirios, and his four daughters Hygieia (= goddess of health; the word hygiene derives from her name), Aceso (= goddess of the healing process), Iaso (= goddess of healing), and Panacea (= she who heals everything). The members of his family included his younger son Telesphoros (= he who brings to fulfilment) who protected convalescing patients.

The sanctuaries of Asklepios were called Asklepieia. The oldest Asklepieion was located in Trikke (present-day Trikala), but the most important and well-known one was established at Epidauros. From the sanctuary of Epidauros, the cult of Asklepios spread rapidly throughout the Hellenic world resulting in the establishment of over 200 Asklepieia: From Kos and Pergamon in the East to the Greek colonies in Cyrenaica, Southern Italy, and even to Rome.

TREATMENT / SCIENTIFIC MEDICINE

Scientific medicine, influenced by philosophy, began to develop alongside theurgic healing. From the 6th c. BC, the Pre-Socratic philosophers, rejecting mythological explanations, were using rational thought to interpret natural phenomena. They extended their thinking to the interpretation of human phenomena – such as health, disease, healing, and death.

Around 500 BC, the natural philosopher Alcmaeon of Croton was the first to define health as the isonomia (i.e., equality and balance) of the opposed powers of the body (hot – cold / dry – wet / bitter – sweet). Thus, whenever any one of these powers prevails over all the others, this creates monarchia, which leads to illness. Consequently, to heal the organism one must restore the balance of these powers.

According to the philosopher Empedokles (5th c. BC) the four components of the universe – and hence of man – are Fire, Air, Earth, and Water. Hippocrates (460 – 375/351 BC), influenced by this philosophical concept arrived at the Humoral Theory. He maintained that the human body contained four humours, or bodily fluids, (blood, phlegm, yellow bile, black bile) and each humour had a qualitative attribute (hot, cold, dry, wet), which corresponded to one of the four components of the universe. Eukrasia, the harmonious balance or blending of the four humours, constitutes the main feature of health. Conversely, the disruption of this balance (dyskrasia) leads to the onset of various diseases.

Thus disease, escaping the purview of divine powers, began to be attributed to natural causes, to factors associated with the environment, age, weather conditions, living conditions, and, generally, with how people live.

HONOURING PHYSICIANS

The institution of the public physician dates to the 6th c. BC, when certain Greek cities first regarded the health of their citizens as a societal obligation. Using high remunerations and other privileges as the lure, the cities sought to attract renowned physicians – whom they would contract with for a specific time period – to care for their citizens in times of war, epidemics, and natural disasters. One such contract is recorded on the bronze tablet from Cyprus.

We also have records, however, of instances where a tax, the iatrikon (medical tax) was used to apportion the expenses of a public physician among the citizens. Some physicians also viewed their appointment to this position as just a stepping stone leading to more profitable employment either by a larger city or by wealthier patients, in the court of a ruler, for example.

To date, the earliest case of a salaried public physician we are aware of is that of Demokedes of Croton, who around 530 BC, was hired for a large sum by the island of Aegina. However, two years later, when Athens offered him more money, Demokedes abandoned Aegina, just as he would later abandon Athens, when Polycrates, the tyrant of Samos, lured him away with an even higher salary.

Consequently, physicians were evaluated based on the fame they acquired through their therapeutic achievements. Moreover, the concept of professional training did not exist in antiquity in its current form, just as there were no diplomas or certificates of accomplishment. The most accessible way of learning a trade was to apprentice to someone who has mastered it; frequently, it was the father who taught the son. Hippocrates himself apprenticed at his father’s side and later taught his own sons.

LENDERS TO THE EXHIBITION

Athens, Ancient Agora Museum (1st EPCA)

Athens, Epigraphical Museum

Athens, Kerameikos Museum (3rd EPCA)

Athens, Museum of Cycladic Art

Athens, National Archaeological Museum

Athens, Numismatic Museum

Abdera, Archaeological Museum (31st EPCA)

Aedipsos, Archaeological Collection (11th EPCA)

Aiani, Archaeological Museum (30th EPCA)

Chios, Archaeological Museum (20th EPCA)

Corinth, Archaeological Museum (37th EPCA)

Delos, Archaeological Museum (21st EPCA)

Dion, Archaeological Museum (27th EPCA)

Epidauros Asklepieion, Archaeological Museum (4th EPCA)

Eretria, Archaeological Museum (11th EPCA)

Herakleion, Archaeological Museum

Komotini, Archaeological Museum (19th EPCA)

Kos, Archaeological Museum (22nd EPCA)

Paros, Archaeological Museum (21st EPCA)

Ptolemaida, Anthropological and Folklore Museum

Pythagoreion on Samos, Archaeological Museum (21st EPCA)

Rhodes, Archaeological Museum (22nd EPCA)

Thessaloniki, Archaeological Museum

Velvendos, Archaeological Collection (30th EPCA)

Nicosia, Cyprus Museum

Paphos, District Museum

Copenhagen, Nationalmuseet

Copenhagen, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France

Paris, Musée du Louvre

Bologna, Museo Civico Archeologico

Florence, Museo Archeologico Nazionale

Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale

Ostia, Museo Archeologico

Rome, Musei Capitolini

Taranto, Museo Archeologico Nazionale

Leiden, Rijksmuseum van Oudheden

London, British Museum

Oxford, Ashmolean Museum

THE CATALOGUE

Exhibition catalogue which contains comprehensive introductory texts written by distinguished scholars, entries with detailed descriptions and photos of all exhibits and full bibliography.

Editors: Nicholas Chr. Stampolidis, Yorgos Tassoulas

CYCLADIC FRIENDS

BE

FRIENDS

CONTRIBUTORS

Curators

Yorgos Tassoulas, Curator, Museum of Cycladic Art

SPONSORS

SANOFI

MAJOR SPONSORS

Chiesi

Eurolife

EFG

SPONSOR

Famar

Novartis

Pharmathen

SUPPORTERS

abbvie

Ferring

Lanes

Menarini Diagnostics

proton

uni-pharma

3E

OFFICIAL AIR CARRIER

AEGEAN

HOSPITALITY SPONSOR

St. George

WITH THE KIND SUPPORT OF

City of Athens

MEDIA SPONSORS

MEGA

ΕRΤ

proto programa

trito programa

KATHIMERINI

madame figaro

Athens Voice

insider

THE TOC

Health Daily

in2life.gr

popaganda

ελculture

doc.tv

protagon,gr

pepper 96.6

athina 98.4

deBop.gr

artmag

iefimerida