Ancient Greek Art

Scenes from daily life in antiquity

PERMANENT EXHIBITION

ON VIEW

The Exhibition, which is enriched with educational material, allows visitors to examine the public life of the ancient city, the religious and funerary customs, and the daily activities of men and the lesser-known world of women through the objects of the Exhibition and the rich visual material.

The nine sections of this Exhibition present the world of gods and heroes and the world of mortals. In each showcase, ancient objects are presented in a setting that contextualizes their use and function. The gallery ends with the screening of two short films and a representation of a coastal municipality in 5th century BC Attica – where, according to the script, Leo, the hero of the films, lived and died. The almost-cinematic gallery allows visitors to feel as if they are walking through an ancient city.

GODS AND HEROES

The ancient Greeks worshiped many gods, lesser deities, and heroes. Additionally, the ancient Greek gods resembled humans and exhibited the needs, desires, and failings of mankind – although they were immortal.

People believed that the gods meddled in the lives of humans, bringing both good and ill fortune. To maintain their favour, worshippers offered votive offerings and made sacrifices, and religious festivals and athletic competitions were held in their honour.

Animal sacrifices frequently occurred in the sanctuaries of the gods – often at an altar in front of the temple. The worshippers offered part of the animal to the god and consumed the remainder.

ON THE WINGS OF EROS

In Hesiod’s Theogony, Eros is a primal creative force that sprang from the primordial deity of Chaos. He personifies the irresistible attraction of all creatures that causes the fury of procreation. Hesiod described him as the fairest among the gods – who loosens the limbs and subdues both mind and sensible thought of both gods and men.

In Plato’s Symposium, Eros appears as a philosopher who continuously seeks fulfilment through intellectual contemplation; this leads him to wisdom and, eventually, to eternal and imperishable transcendental beauty.

At Thespiae, Eros was worshiped as a fertility god, and, in Athens, he and Aphrodite had a joint cult following.

TOILETRY AND WEDDING

Girls tended to marry at about 14 – often to men twice as old. The bride’s father arranged the marriage without asking for the consent of his daughter in the choice of the groom. The betrothal – an oral agreement between the bride’s father and the groom that was sealed by a handshake – and the subsequent dowry were integral aspects of a lawful marriage. In case of divorce, the dowry was returned to the bride’s family.

Marriage also entailed a woman’s transfer from the authority of her father to that of her husband. The ultimate purpose of marriage was to produce legitimate children – preferably male – to continue the family line and ensure the inheritance of property.

WOMEN’S ACTIVITIES

Women were confined to the women’s quarters of the house, which were located on an upper floor. It was believed that only by isolating women this way could men guarantee the fidelity of wives, therefore ensuring the legitimacy of future heirs.

The most important duties for a woman in ancient Greece were to raise her children and run the household. Women had very limited freedom outside the home; they could only fetch water from the public fountains, attend or participate in some religious festivals, and visit the tombs of family members.

The courtesans were the only women that could really enjoy their freedom, attend symposia, and administer their own properties.

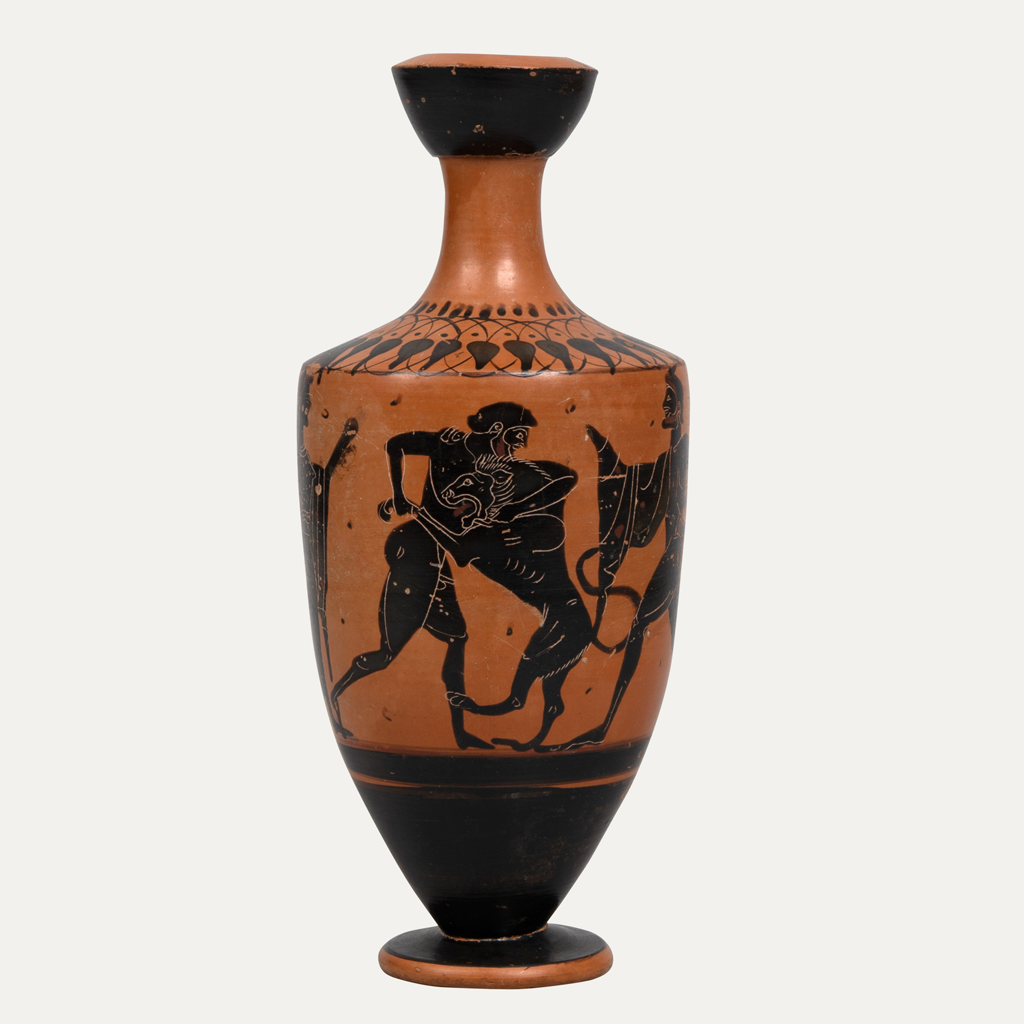

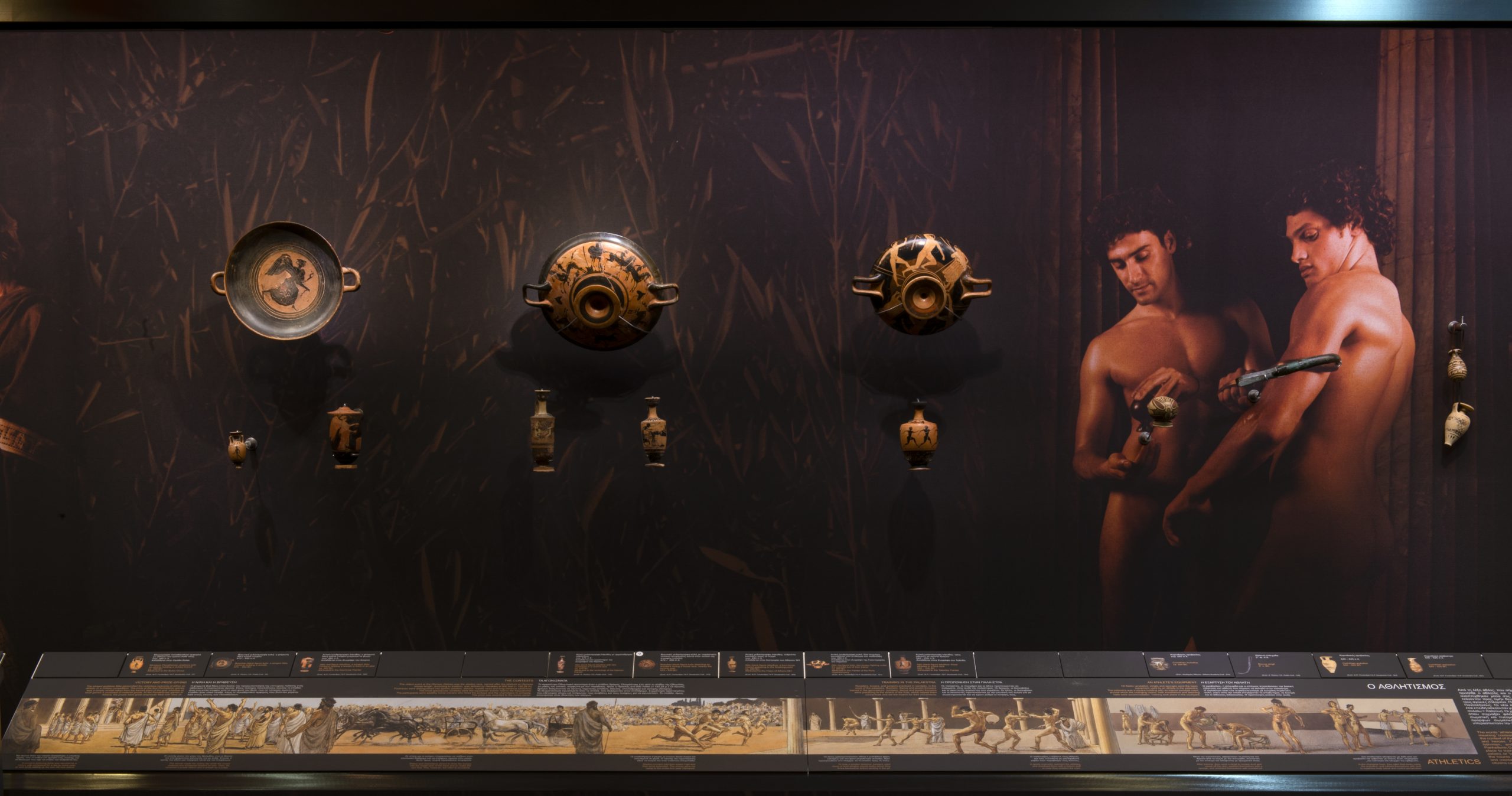

ATHLETICS

The words “athlete” and “athletics” derive from the ancient Greek word, άθλος, meaning “contest for a prize”.

Athletic competitions developed in the context of major religious festivals that were held in honour of gods and heroes. Four of these events (the Olympic, Pythian, Isthmian, and Nemean Games) attained the prestigious status of Panhellenic Games.

Male youths trained in the Gymnasion (lit. a place to train in the nude) and the Palaestra (from the Greek παλαίω, meaning “to wrestle”). The training grounds were also schools and the haunts of philosophers, musicians, and sophists. Physical and mental exercise aimed at producing healthy and virtuous citizens who were capable of defending their city.

SYMPOSIUM

Symposium comes from the Greek symposion, meaning “communal drinking”. Communal meals appeared in Greek cultural history as informal gatherings of aristocratic friends –where food, wine, conversation, and singing were essential elements.

The symposium flourished in antiquity beginning in the early 7th century BC and was an important social institution. An exclusively male affair, the symposium served to strengthen the bonds between the participants. Additionally, the symposiasts avoided excessive wine-drinking; they drank enough just to make them merry but still intellectually sharp to discuss political and philosophical issues, to perform poetry, or to amuse themselves with erotic games.

IN THE ATHENIAN AGORA

In ancient Greek, agora means “a place of gathering”. The Athenian Agora, which was located on the north-west slopes of Acropolis, was the birthplace of democracy and flourished following the constitutional reforms of Kleisthenes in 508/7 BC.

Citizens gathered in the Agora to participate in their city’s governance, decide judicial matters, express their opinions, and elect their officials. It also served as a marketplace where merchants and artisans sold their goods and a place of religious activities, theatrical performances, and athletic competitions. For centuries, the Agora was the administrative and commercial heart of Athens.

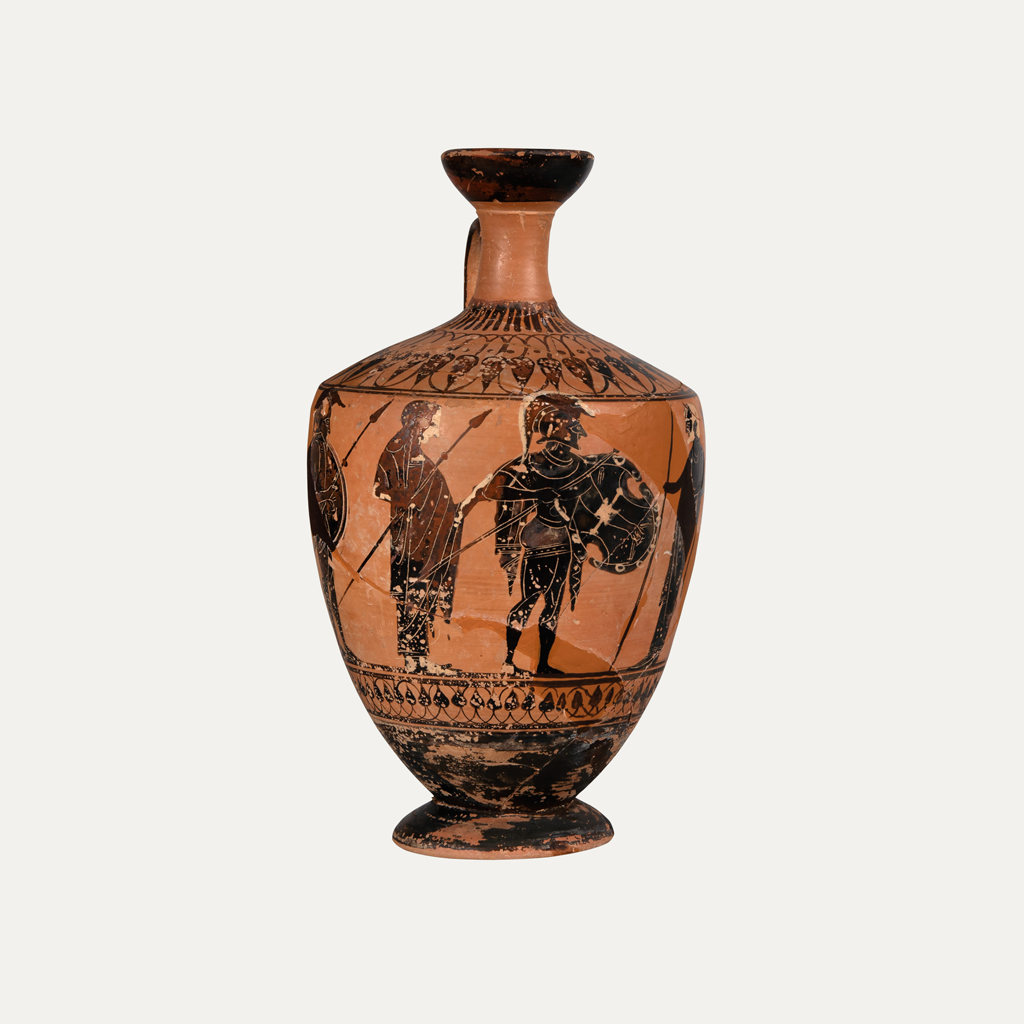

WARFARE

The main occupation of all fit, adult men was to develop in the art of warfare. From a young age, men started to practice warfare techniques in order to always be ready for battle, either through daily training in the palaestra or through hunting.

The wars against common national enemies – as well as other city-states – contributed to the development of weaponry as well as the improvement of warfare methods and tactics.

A warrior’s defensive armour included a shield, a breastplate, a helmet, and a pair of greaves. Offensive weapons such as spears and swords were used in close combat, whereas slings, bows, and javelins were used to throw from a distance.

TAKING CARE OF THE DECEASED

In Classical Greece, burial rituals consisted of three acts. First, there is the laying out of the body on a bed at home so that the family could mourn. Then, on the next day, the body – escorted by a procession of relatives – was taken to the cemetery. Finally, the last stage was the inhumation of the corpse – or the deposition of its cremated remains in a cinerary urn – along with the grave goods.

Inhumation and cremation were practiced concurrently from the 8th to the 4th centuries BC, and the predominance of one method over the other varied from place to place, according to the social status of the deceased.

The grave, usually marked by a marble stele, was regularly visited by female relatives, who would bring offerings to the dead.