Kykladitisses:

Untold stories of women in the Cyclades

ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXHIBITION

FROM DECEMBER 12, 2024 UNTIL MAY 4, 2025

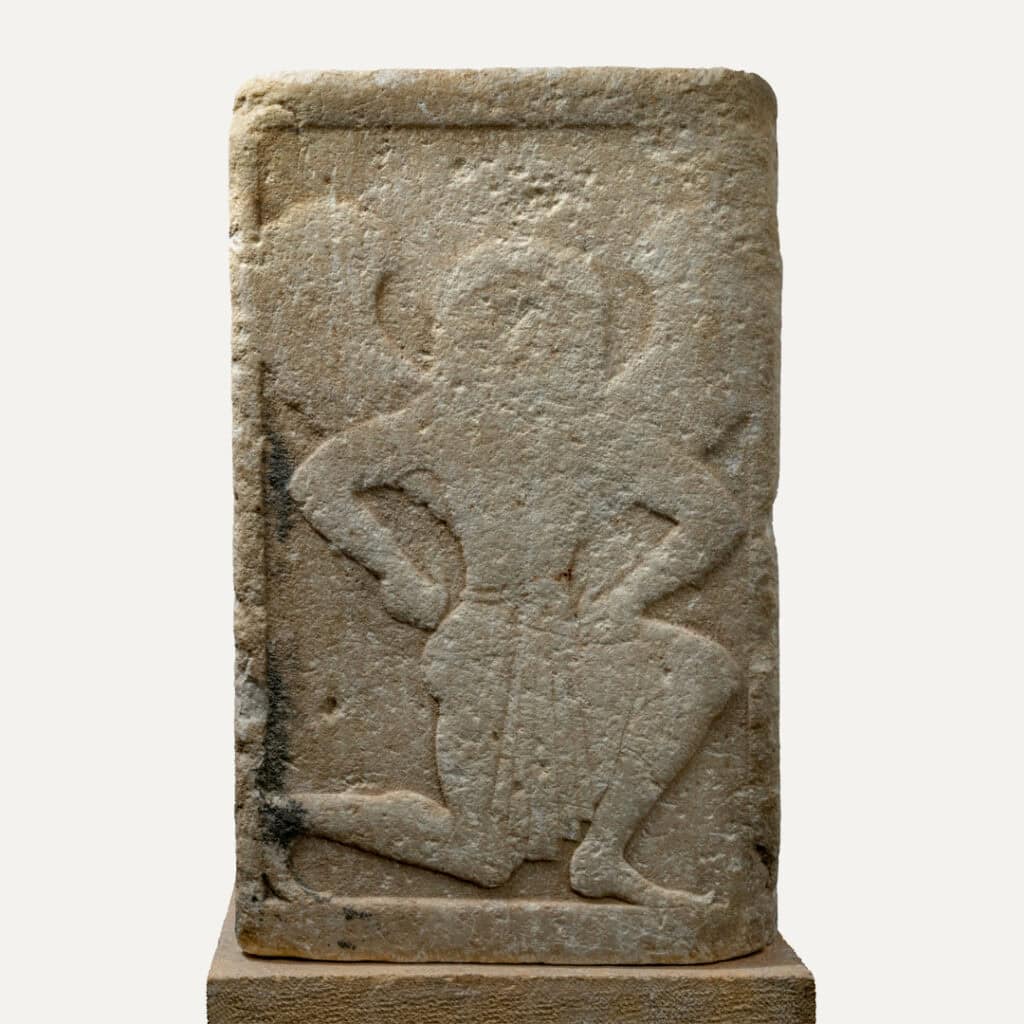

JUGGLING BETWEEN GENDERS

The section examines the concept of gender in Cycladic societies, something that in antiquity was neither strictly nor completely separately defined. Three important exhibits in the art of the islanders of the Archipelago capture this fluidity of attitude.

A relief from Delos depicts Dionysus in the attire of Artemis, the main goddess of the island. The figurine from Despotiko testifies that in Cycladic art the figure of Artemis is often conflated with that of her twin brother, Apollo. A marble weight from Delos bears a relief representation of Hermaphroditus, the individual who defines the transition point between the two sexes.

GODDESSES OF THE ISLANDS

The worship of female deities has always been a central element of the religious and cultural identity of the islands of the Archipelago.

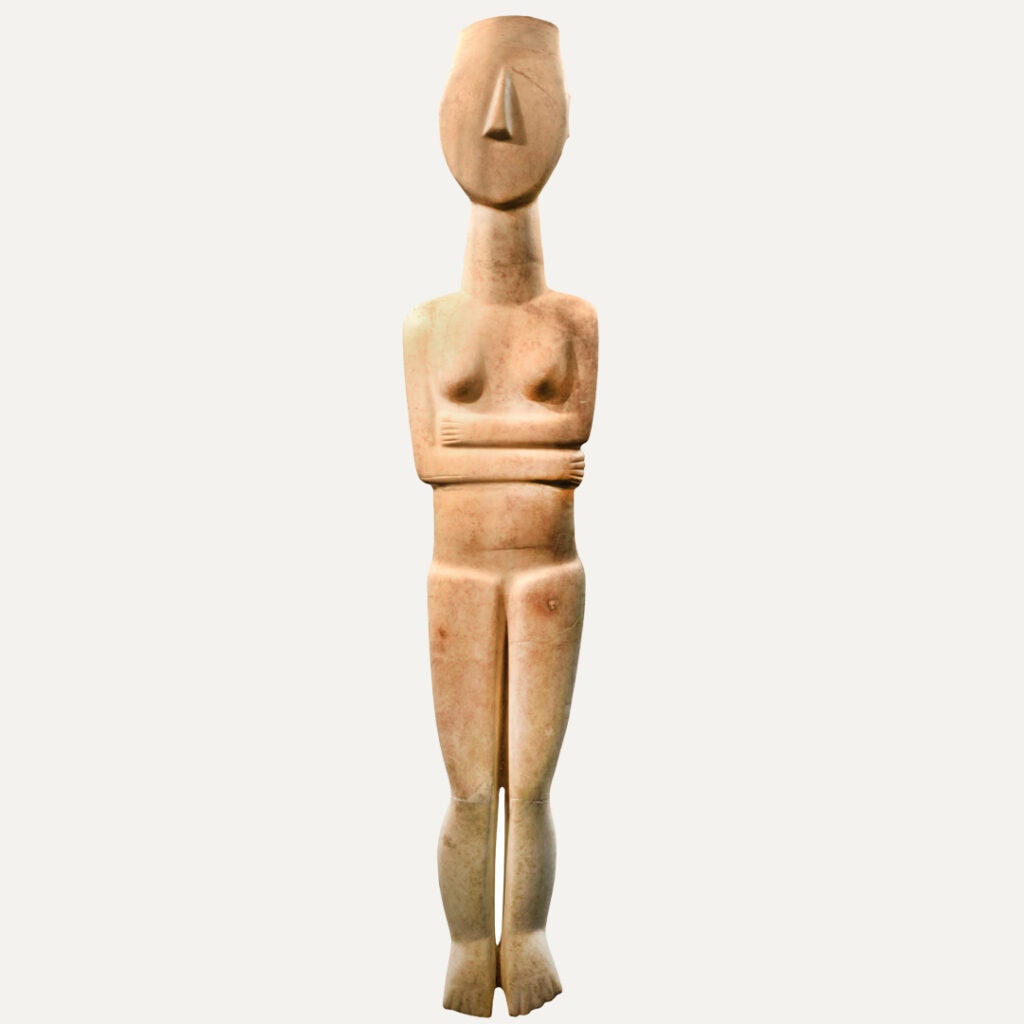

The Neolithic female figurines with their accentuated anatomical features associated with fertility reflect the first appearance of the worship of a Great Mother-Goddess, who symbolized fertility and rebirth. A Goddess who in the 3rd millennium BC was carved in marble with her hands folded over the abdomen that holds life within it.

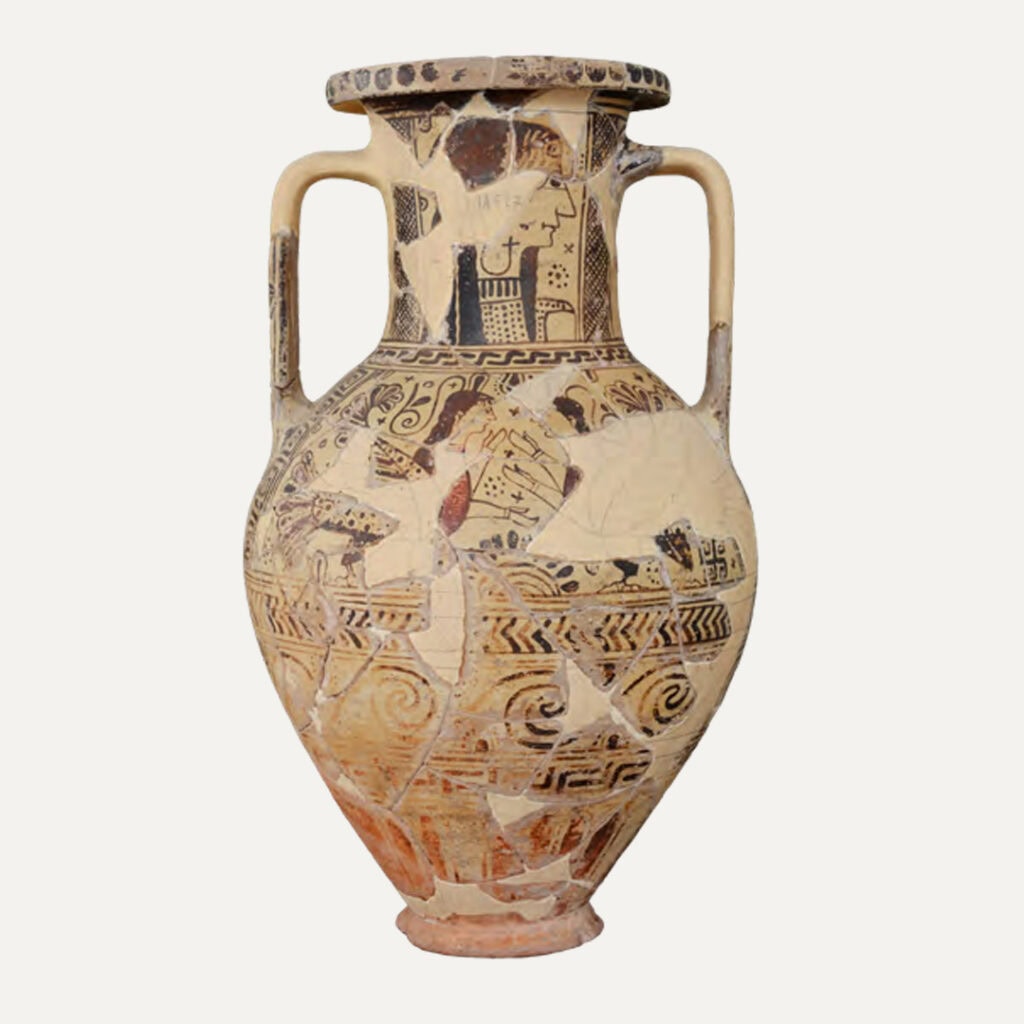

This Mother-Goddess evolves through time and becomes “Potnia of Theron” or the “Mistress of Animals”, often shown with her arms raised, flanked by wild animals.

Eventually, one of her main expressions is seen in Demeter, the goddess of agriculture, whom the inhabitants of the Cyclades worshipped, dedicating sanctuaries to her on many islands.

On Delos, however, in the centre of the Cyclades, the dominant goddess is Artemis, the goddess of hunting and wildlife. An exceptional statue of the goddess – travelling outside the island now for the first time to tell its story – shows her as Elaphebolos (killing a deer).

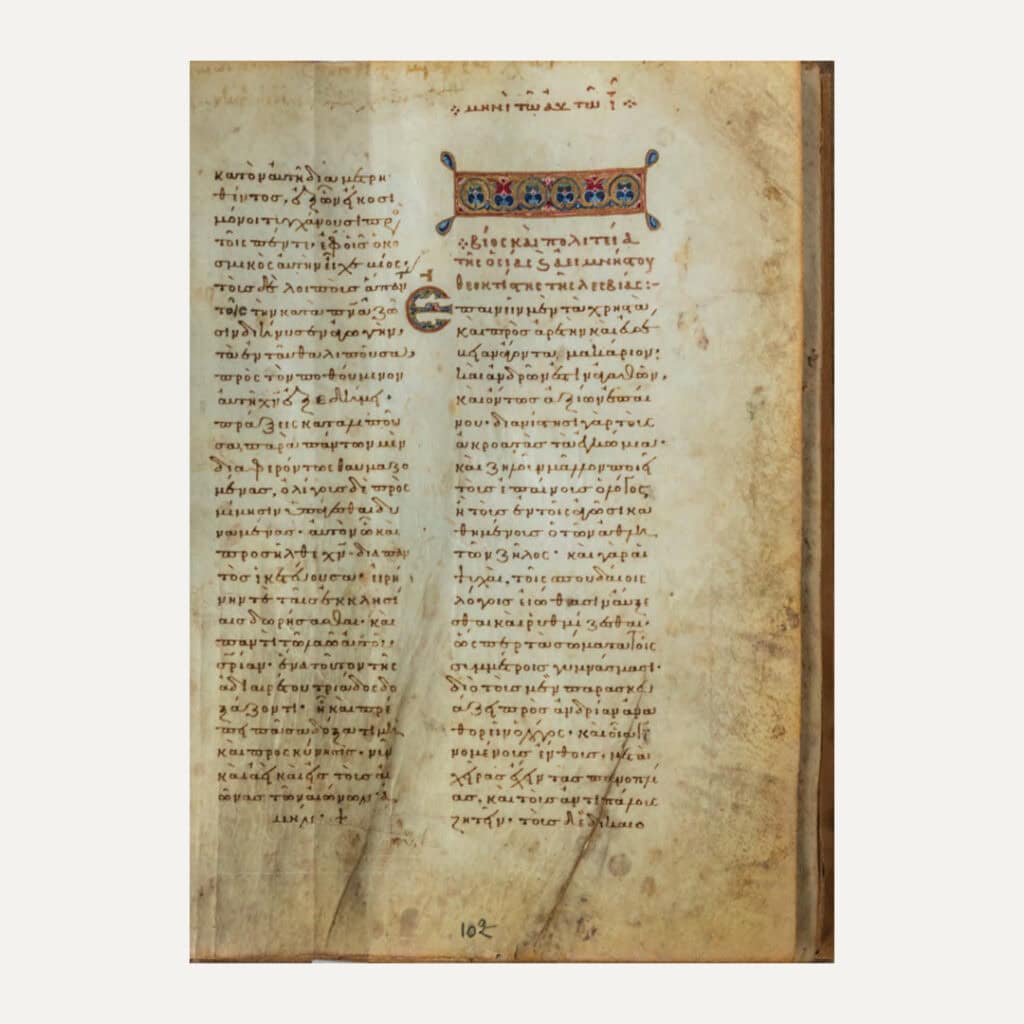

IN THE SANCTUARIES

The section focuses on the leading role of women of the Cyclades in matters of religious worship, mainly as priestesses and as worshippers.

The emblematic fresco of the Women in the adyton (“Adorants”) from Akrotiri of Thera dated in 1600 BC depicts an initiation ceremony of a young girl joining the adult world. Behind her are two women, one on the left holding a necklace and one in the centre who is shown wounded, having injured her foot on a rock and bleeding. From the drops of blood, a crocus flower springs up, towards which she turns her hand, as if seeking to heal her wound with it. It is a gesture that both emphasizes the miraculous birth of the flower from the blood of a woman-goddess and highlights the healing properties of the plant. For the first time in this exhibition, the bleeding woman is set side by side with Saint Anastasia the Pharmakolytria (“Deliverer from Potions”) from Naxos. Though 3000 years separate them, the timeless capacity of women to heal through faith is here made plain to see.

The famous Korai of Kea, wearing their ceremonial garments, seem to be dancing in anticipation of the appearance of the goddess they worship. They move and sway just as do the women depicted on the lebes gamikos (a vase used in wedding ceremonies) from Rheneia, who perform the “Dance of the Deliades” in honour of Apollo and Artemis.

Over the centuries, images of women, such as the impressive Archaic Kore of Thera – here presented to the public for the first time – were dedicated as offerings or funerary monuments to honour a goddess or a deceased woman of Thera, so becoming symbols of power or social order.

FEMALE APOTROPAIC FIGURES

In art, the inhabitants of the Cyclades sometimes use women as an image evoking “fear” in the beholder. These beings take the form of female hybrid creatures of an apotropaic-protective character.

Some were Sphinxes, who had the head of a woman, the wings of a bird, the body of a lion, and who embodied powers that frightened mortals.

Others were the Sirens, who had a woman’s face and a bird’s body. They were creatures of the sea that lured sailors to destruction with the seductive sweetness of their songs. The islanders, surrounded by the Aegean Sea, naturally depicted them often in their art.

Gorgon with her serpentine hair, which turned anyone who saw her into stone, was also popular in the Cyclades, as her myth was associated with the lord of Seriphos, Polydektes.

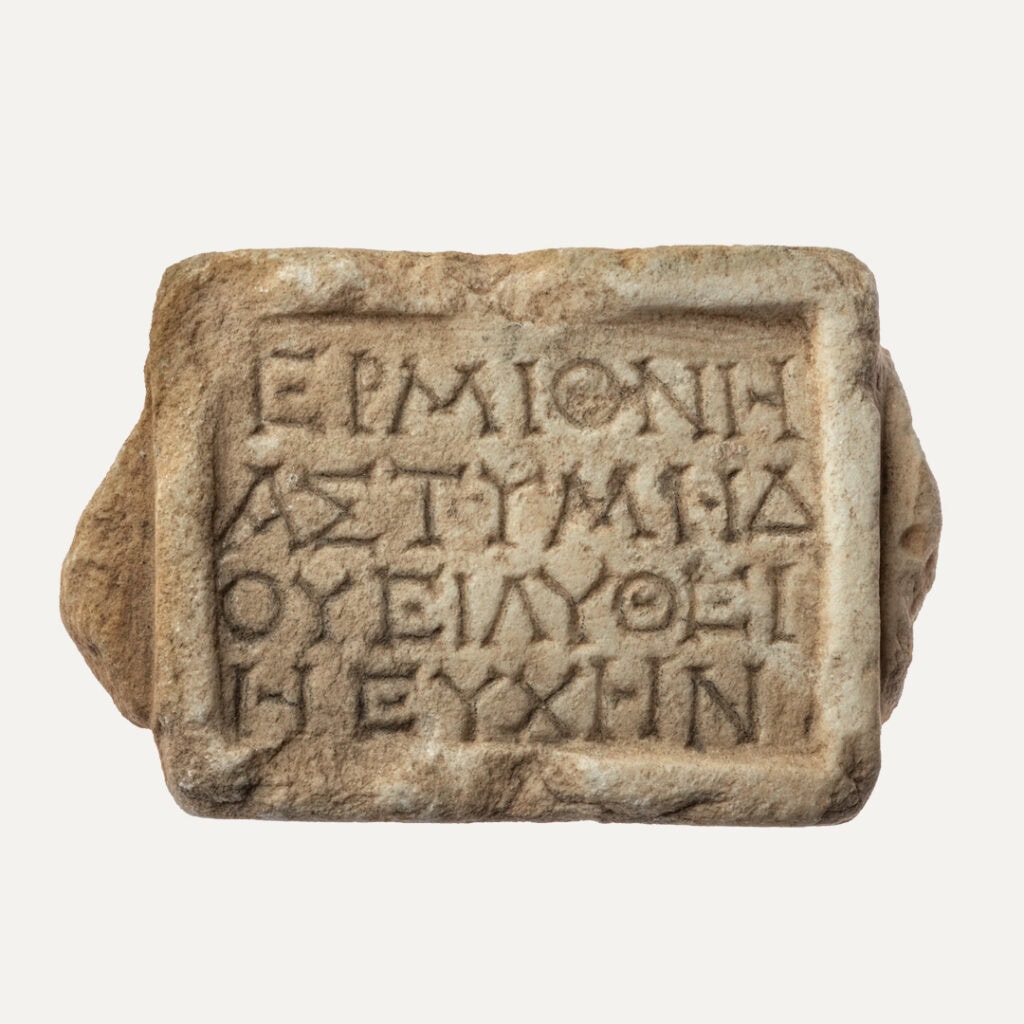

FEMALE IDENTITIES

The section dives deeper into the world of Kykladitisses (Women of the Cyclades) by examining their multiple identities and the limitations imposed on them by society.

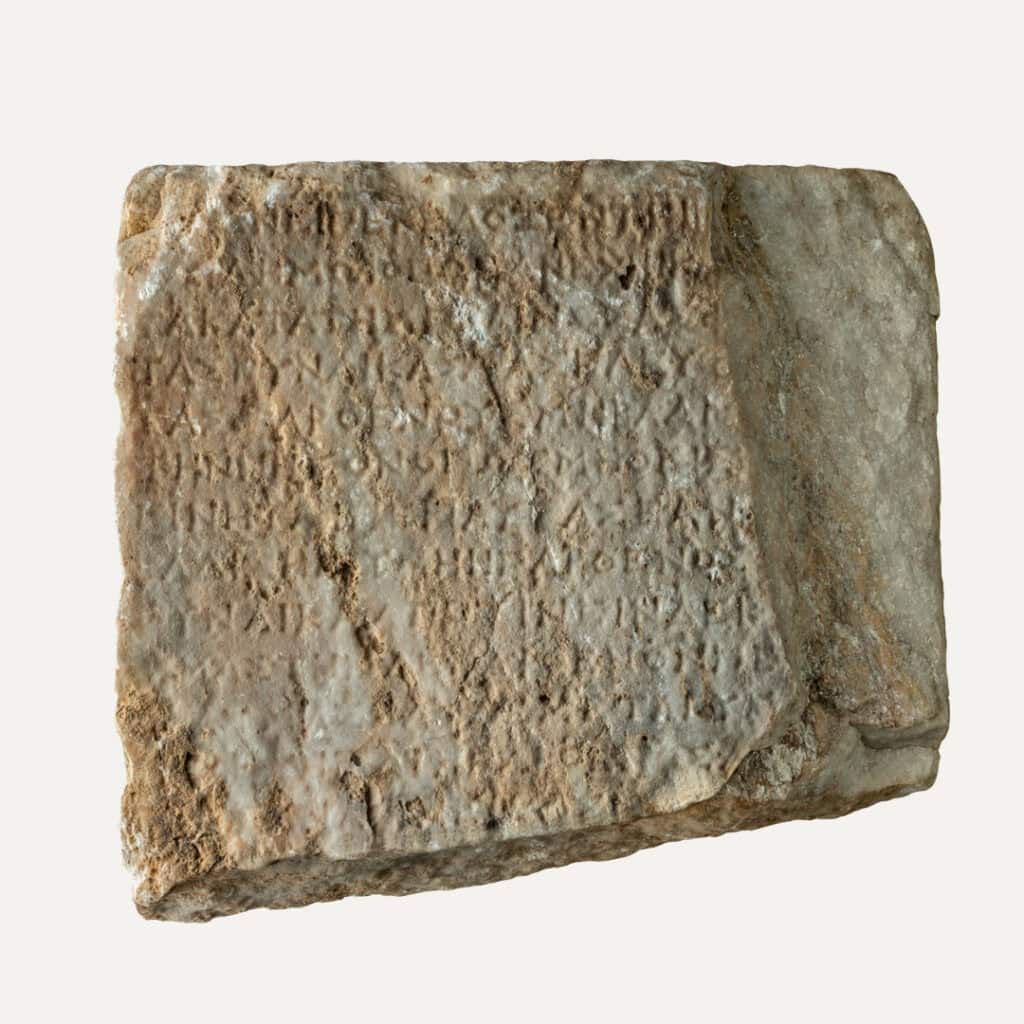

A typical example is a stele from Kea with a decree related to the controlling the movement of women from Karthaia in the 3rd century BC.

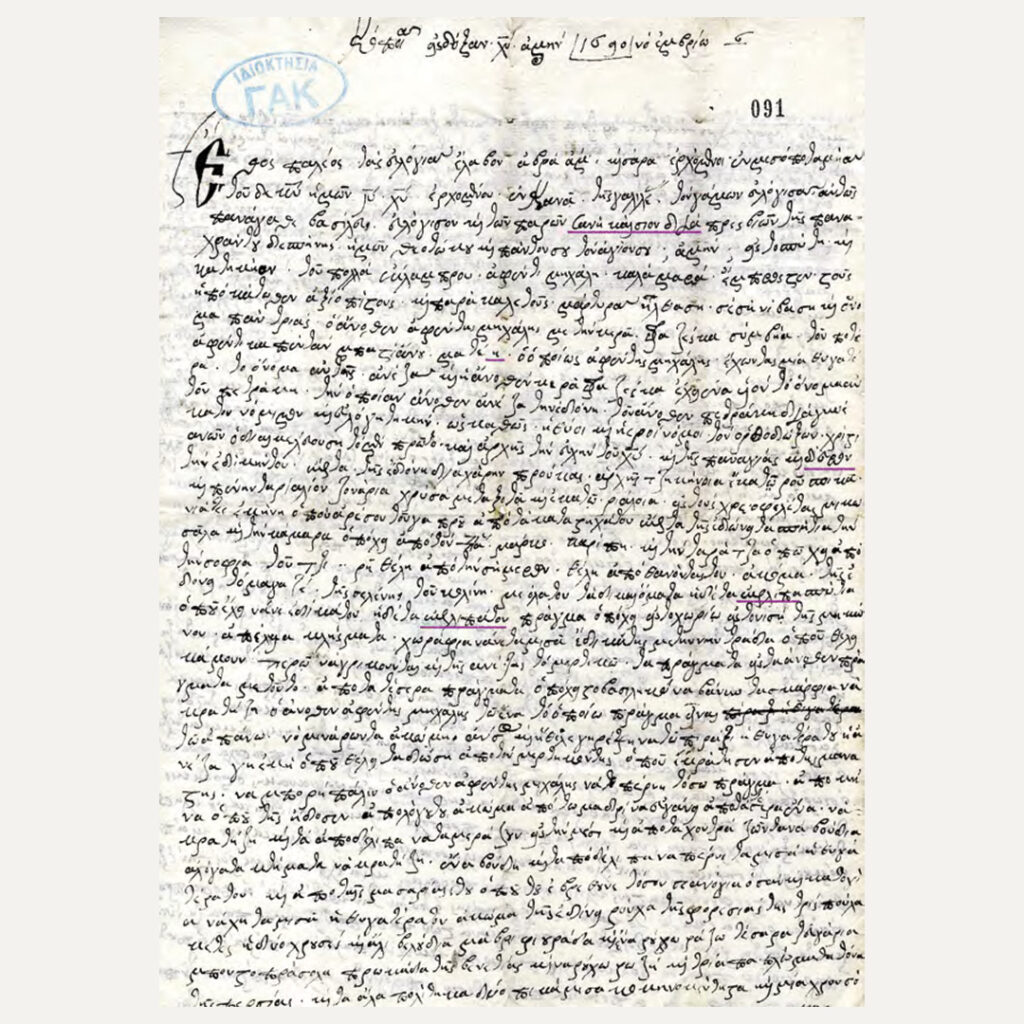

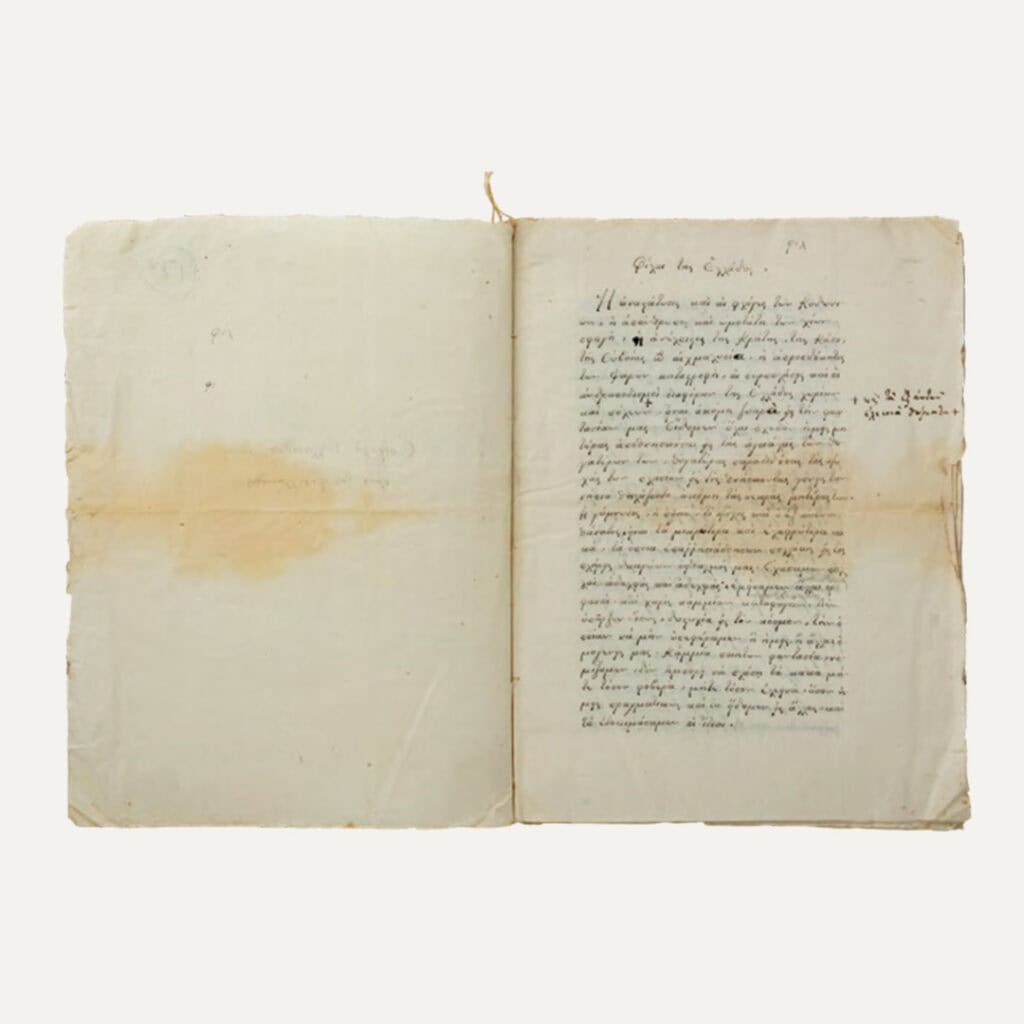

With marriage, a woman passed from the ownership of her father to that of her husband. The dowry offered by the father to the husband confirms this view, as can be seen from a 3rd century BC stone stele from Mykonos. A manuscript dowry document of 1690 AD from the same island bears witness again that this tradition continued for many centuries later.

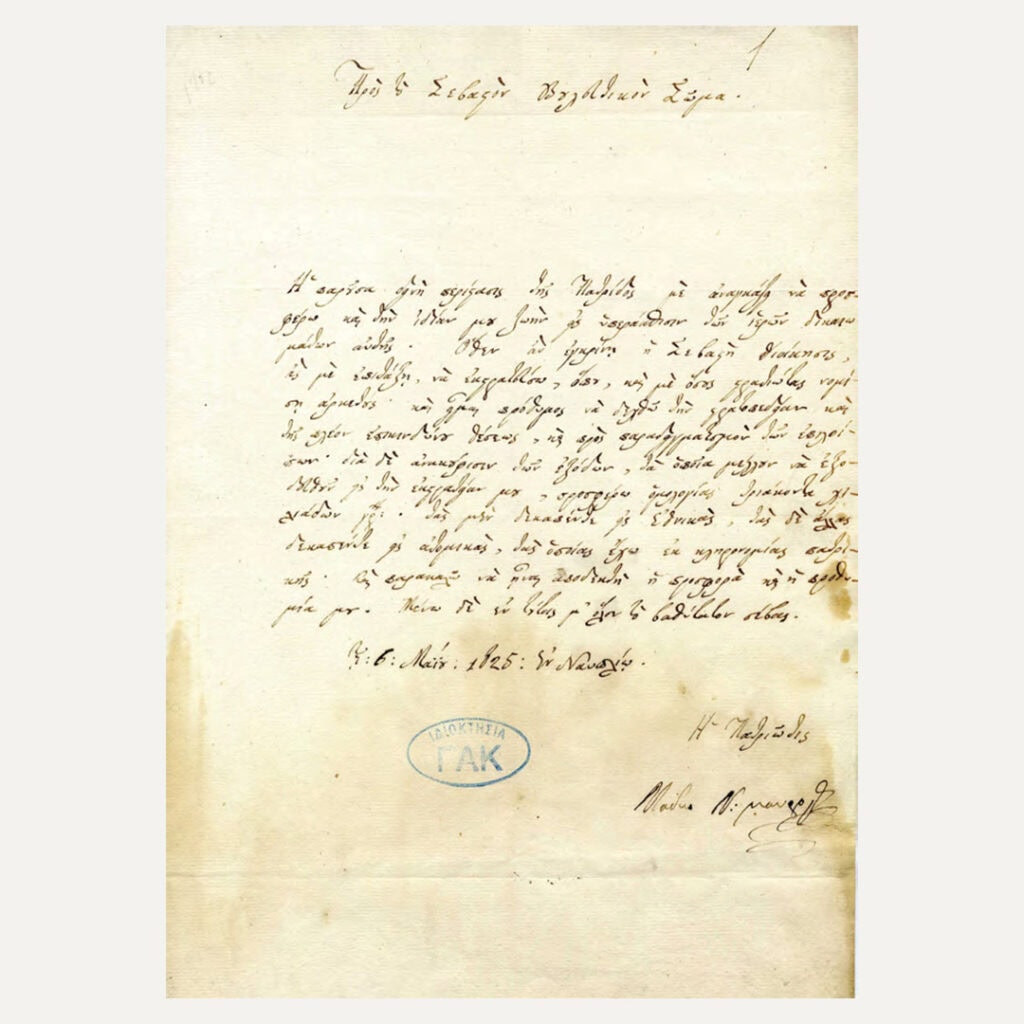

From time to time, however, the woman of the Cyclades experienced moments of relative emancipation. As early as the Hellenistic period, a general improvement in her social status was marked, which would become more visible during the Roman period. At the dawn of the birth of modern Greece, Kykladitisses, such as Evanthia Kairi and Manto Mavrogenous, were the pioneers of the new status claimed by women.

GODDESSES OF THE SEA

In the field of religion, the female deities and saints become one with the Cycladic land and seascapes, acquiring new properties relevant to the cult needs of the islanders. Isis, in the Cyclades, becomes “Pelagia” and protects sea voyages by providing favourable winds.

The goddess, in her maritime capacity, lives on in the Virgin Mary of the Christian faith, who is depicted in icons as the protector of sailors and sea voyages.

EROTICISM

Women have always been associated with matters erotic, the main deity of which was Aphrodite. The goddess of love, invoked as Aphrodite Pandemos, symbolized the carnal union between man and woman, a union that is vividly depicted in the art of the Archipelago.

VIOLENCE

Kykladitisses undoubtedly experienced gender violence in the patriarchal societies of the islands. Such violence was strongly reflected in ancient Greek art and mythology, giving the impression that it was “normalized”, that it was accepted.

A mosaic from Delos depicts the Thracian king Lycurgus preparing to strike with a double axe the fallen nymph Ambrosia, who has refused his sexual advances. From the same island comes a marble group depicting Poseidon pulling off the nymph Amymone’s garment to undress her.

A funerary stele depicts Aline, a traveller who arrived in Delos from distant Phoenicia and was buried in Rheneia, dying while pregnant. The monument is a moving expression of how an immigrant woman became a Kykladitissa – as fate willed, falling victim to a possibly violent death.

DEATH THROUGH THEIR OWN EYES

The art of the Cyclades reveals the main role women played in funeral customs. Women mourned and showed their grief by wearing black clothes, pulling their hair and beating their breasts. Time and again, they knelt in front of the grave, unable to bear the harsh reality.

Many Cycladic monuments are coming to light, revealing how the woman of the Cyclades coped with the loss of a loved one. A typical example is the case of Damokleia from Thera, who erected an imposing funerary monument for her lost sister Parthenika, who had passed away before her time.

Another epigram from Amorgos bears witness to a mother’s grief at the untimely loss of her daughter, Vitti.

FROM THE OIKOUMENE TO THE ARCHIPELAGO

The Cyclades, due to their privileged geographical position, have always been an important hub that attracted people from all over the world. Women of different origins, like many immigrants, arrived and settled in the Cycladic islands, leaving their mark on the history of the Archipelago.

A stone statuette from Egypt bears witness to the relations of the Cyclades with the land of the Pharaohs and depicts Nesnephthys, which offering some people had dedicated to the goddess Isis, in the Sanctuary of the Egyptian Gods of Delos.

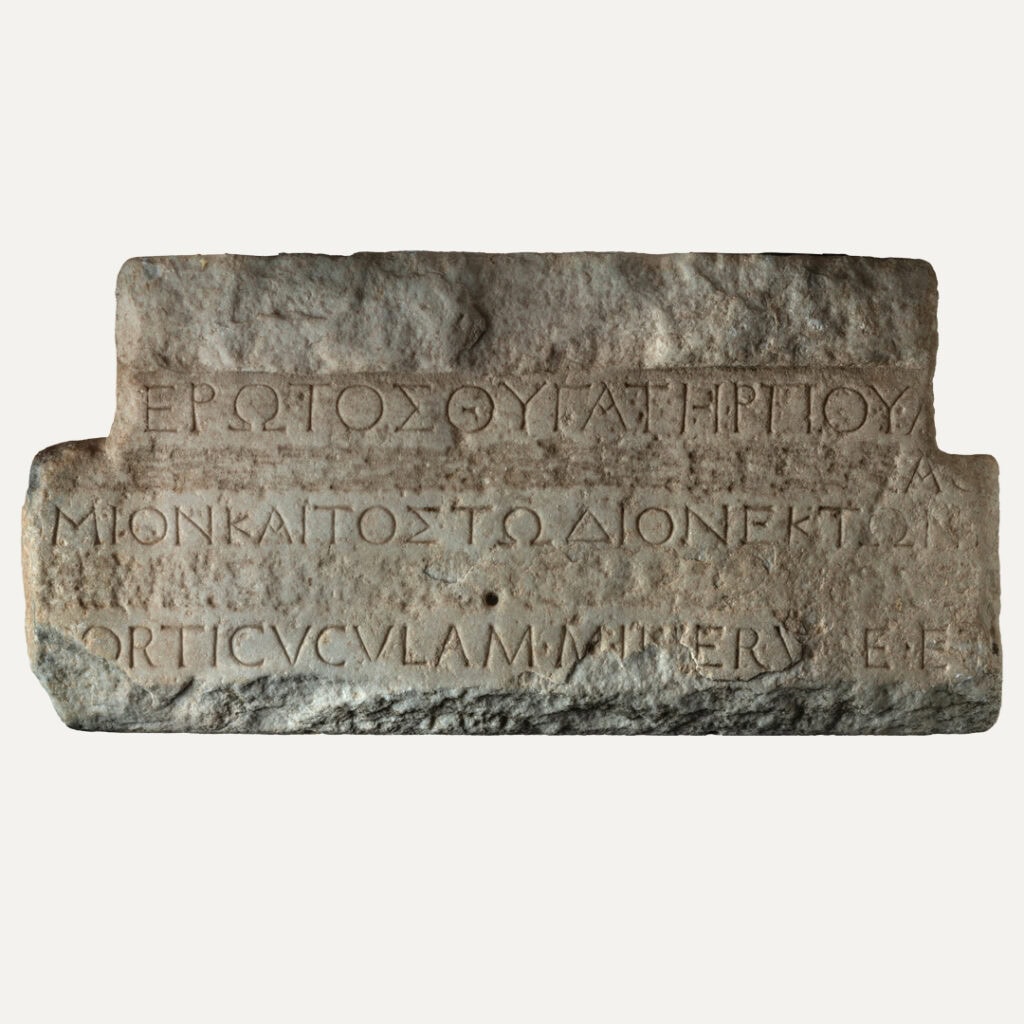

Then there is Magia Pulchra, a Roman freedwoman, who became a Kykladitissa and financed important public buildings in Melos, thus offering her generous services to her new homeland. She too is characteristic.

Another female traveller was Osia Theoktiste from Lesbos, who was violently removed from her native land and ended up on Paros, dedicating her life to God.

THE ORIGIN OF THE WORLD

Woman as the bearer of life was depicted remarkably often in the marble Cycladic figurines of the 3rd millennium BC. They display their once swollen bellies or the lines inflicted by childbirth, being so associated with the worship of a Great Mother-Goddess, who controlled both life and death.

Childbirth in antiquity was an extremely important process for the perpetuation of society, but at the same time a very dangerous one. For this reason, women used to dedicate various votive reliefs, depicting parts of their body to the sacred deities associated with fertility.

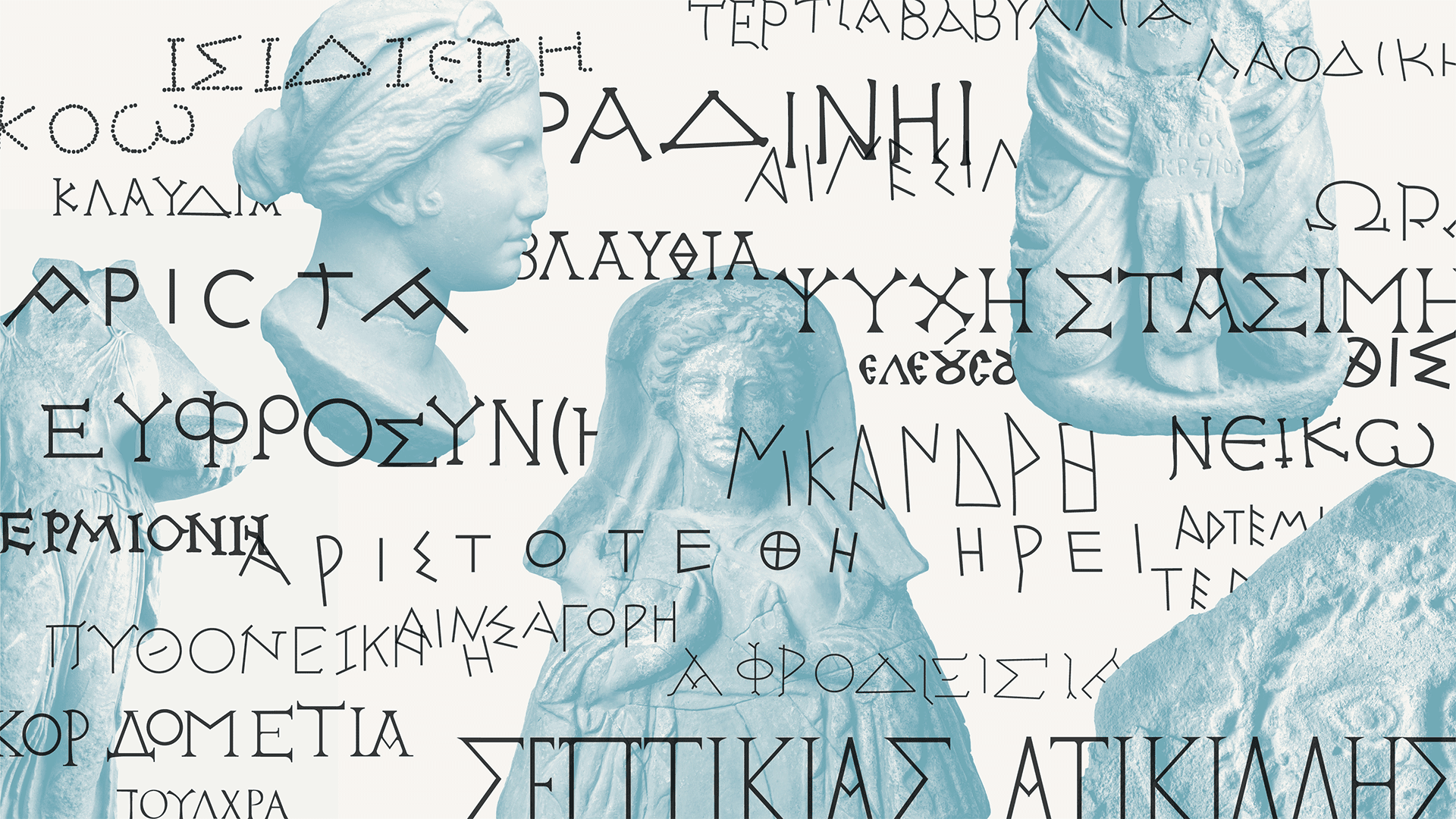

FACES

Over time, Cycladic women experience various transformations. The simple marble figures first take on the face of deities of unparalleled beauty and power that then give way to powerful empresses and saints.

Multiple social roles reflect the evolution of the female figure in the heart of the Aegean that chooses to commemorate them in statues, frescoes and coins, presenting them as an active and integral subject of history.